As the planet fills up with plastic and the EU ponders its new ‘plastics strategy’, is the great re-framing and concern co-option strategy of the plastics industry finally going to run out of road? The threat of invisible omnipresent micro-plastics may force policy-makers to rethink plastic entirely.

It is said that the world’s most viewed image is Microsoft’s ‘bliss’, that unreal looking green hill, blue sky XP background which personally I always found unlikeable and repellent because it shows such complete subjugation of nature. Anyway, according to Seventh Light Studio, by 2017 it was ‘safe to say’ it has been seen over a billion times.

But probably the greatest actual communications dis-service ever done to nature was by a 1970s TV advertising campaign which is said to have been viewed 14 billion times: the ‘Crying Indian’ by Keep America Beautiful.

The pure genius of this highly emotive campaign was that it bought a social licence for mass production of disposable packaging, by championing action to clean up the pollution it led to.

The story is legendary in the annals of advertising and now that hundreds of NGOs are joining forces to try and head off the tsunami of plastic waste invading our environment and our bodies, campaigners should have a good look at it. Try this brilliant article from Orion Magazine by Ginger Strand.

The exact same strategy still sustains the plastics industry and is being used by groups like http://www.plasticseurope.org/ (100+ plastics manufacturers), and the ‘69 plastics organizations and allied industry association in 35 countries’ behind https://www.marinelittersolutions.com/

It is a beautiful, if evil strategy, simple and elegant: once underway it is even cheap to run, as it is powered not simply by petro-dollars but by the active voluntary participation of people who care about environmental pollution. This is true genius. It co-opts the energy, goodwill and emotional commitment of those people, especially the young, who care enough about birds choked on plastic and beaches littered in plastic waste, to spend their own time, at their own expense, picking up the industrial detritus that the plastic industry creates.

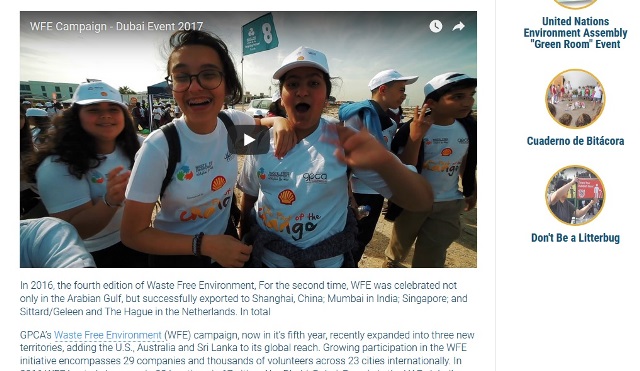

The dark charm of this strategy is that it operates in plain sight, indeed it is intended to be very visible. www.marinelittersolutions.com explains that it has 260 projects ‘planned, underway or completed’ since 2011, such as Waste Free Environment, which started with school children cleaning up plastic in the Arabian Gulf and has now been ‘successfully exported to Shanghai, China; Mumbai in India; Singapore; and Sittard/Geleen and The Hague in the Netherlands’.

Such projects provide something more valuable even than children happily wearing shirts emblazoned with petrochemical logos: they frame and visualise the problem as litter not plastic production, and they suck environmentalist energy into picking it up.

“People start pollution. People can stop it”

Above: the original tv ad, featuring actor ‘Iron Eyes Cody’, not actually an Indian although he adopted an alter ego as one and has been much written about. It was launched on Earth Day 1971, one year after the first Earth Day in 1970, seen by many as the start of the ‘modern’ environmental movement.

The framing is obvious but it has served the manufacturers of packaging well for nearly sixty years. ‘Crying Indian’ made individual consumers responsible, not the manufacturers, wholesalers or retailers. It then motivated individuals to accept and act on that responsibility for ‘littering’. Its success is measured in the many millions who take part in litter clean-ups without challenging plastic production, and in the framing, for example, of marine plastic pollution as ‘marine litter’ in the research, the Marine Strategy Framework Directive, and now the plans for its ‘Plastics Strategy’, by the European Commission. Like a spreading ‘meme’, when a strategic frame colonises our thinking ranging from the European Commission’s ‘Circular Economy’ down to community beach cleans, it simply has to be judged a brilliant success.

Consequently NGO initiatives like #Breakfreefromplastic and #Rethinkplastic which want to challenge the growing production of plastic, have their work cut out.

Roots in the 1950s

Ginger Strand describes better than I can, how this strategy goes back even further than 1971. She points out that in the 1950s, it became US Government policy to stimulate consumer purchasing to boost the economy, and that could be encouraged by replacing reusable things with throw-away things.

Led by beer manufacturers, refillable bottles started to be replaced by ‘throwaway containers’ and ‘many of them were ending up as roadside trash’. Ginger Strand records:

In 1953, Vermont’s state legislature had a brain wave: beer companies start pollution, legislation can stop it. They passed a statute banning the sale of beer and ale in one-way bottles. It wasn’t a deposit law — it declared that beer could only be sold in returnable, reusable bottles. Anchor-Hocking, a glass manufacturer, immediately filed suit, calling the law unconstitutional. The Vermont Supreme Court disagreed in May 1954, and the law took effect. That October, Keep America Beautiful was born, declaring its intention to “break Americans of the habit of tossing litter into streets and out of car windows.” The New York Times noted that the group’s leaders included “executives of concerns manufacturing beer, beer cans, bottles, soft drinks, chewing gum, candy, cigarettes and other products.” These disciples of disposability, led by William C. Stolk, president of the American Can Company, set about changing the terms in the conversation about litter.

By 1957 Vermont was pressured into dropping its reusable bottle law and disposable drinks containers grew rapidly throughout the 1960s. Strand writes:

In 1962, Michigan considered a ban on no-return bottles. Keep America Beautiful openly opposed it. Throughout the sixties, Keep America Beautiful and the Ad Council battled a growing demand for legislation with an increasing vilification of the individual. They spawned the slogan “Every litter bit hurts” and popularized the term “litterbug.” In 1967, meeting at the Yale Club, they decided to go negative. “There seemed to be mutual agreement,” wrote campaign coordinator David Hart, “that our ‘soft sell’ used in previous years could now be replaced by a more emphatic approach to the problem by saying that those who litter are ‘slobs.’” The next year, planners upped the ante, calling litterers “pigs.” The South Texas Pork Producers Council wrote in to complain.

Meanwhile:

At the same time, KAB’s corporate sponsors made sure their own glass containers and cans never appeared as litter in the ads

Then non-corporate members of the Ad Council (an industry foundation organising pro-bono public service ads) revolted and threatened to pull support from littering campaigns. ‘Backed into a corner, KAB directors agreed to expand their work to address “the serious menace of all pollutants to the nation’s health and welfare’.

The result was that an executive from the American Can Company, ‘volunteering’ for Keep America Beautiful, brought in his own company’s agency, Burson Marsteller, who created the seminal Crying Indian ad.

Today, in terms of what we know of human health and ecological threats, the can industry seems a relatively benign influence compared to plastics but www.marinelittersolutions.com is still using the tried and tested tropes, for example with a ‘Don’t Be A Litterbug’ campaign.

The Plastics Story Now

In 2017 scientists from several US institutions calculated that since the 1950s ‘humans have created 8.3 billion metric tons of plastics … and most of it now resides in landfills or the natural environment’. The biggest use of plastics is packaging. Roland Geyer, lead author of the study and associate professor in University of California Santa Barbara’s Bren School of Environmental Science and Management said: “Half of all plastics become waste after four or fewer years of use.”

Ellen McArthur Foundation: The New Plastics Economy

Global plastic production still increases rapidly. Most heads to the environment in landfill or as pollution of seas, freshwater or soils. In 2012 only 9% of plastic was recycled in the US, and 27% in Europe, while it is estimated that globally, 32% is “leakage” (environmental plastic pollution to air, sea, freshwater, soils), 40% is landfilled (from which some of it may still escape), and only 14% is “collected for recycling” of which just 2% is ‘closed loop’ (the European Commission’s vision for a Circular Economy). Clearly there is a vast gap between generation of plastic pollution and recovery for recycling, and almost nowhere (except possibly Finland?) is it being brought under control.

End of the Road?

What may be ending the hegemony of that Burson Marsteller strategy is the demise of ‘litter’ as the main focus of concern. In the last ten years but particularly in the last few years, studies have shown that vast quantities of ‘micro’ and even ‘nano’ plastics are entering the environment and the food chain. All the big bits of visible (macro) plastic break down into microplastic, and then become invisible. Everything from car tyres (made of plastic not rubber) to clothes (nylon, polyester etc) to more obvious types of plastic: bags, bottles etc, is breaking down into invisible tiny fibres and fragments. Deliberate ‘microplastics’ such as abrasives in toothpastes and cosmetics is just a drop in the plastic ocean (less than 4% of microplastics).

Wikipedia states: ‘Microplastics could contribute up to 30% of the ‘plastic soup’ polluting the world’s oceans and – in many developed countries – are a bigger source of marine plastic pollution than the more visible larger pieces of marine litter, according to a 2017 IUCN report’.

It’s only in the last two years that scientists have discovered that most of the plastic entering the oceans is probably ‘disappearing’ because it is ending up in the food chain.

This is not just an aesthetic or wildlife-harming disaster but potentially an economic and sustainability catastrophe. If it also turns out for example that new and hazardous chemical reactions take place on the surface of micro plastics, or they otherwise affect human health, we are in big trouble. The UK CIWEM, the Chartered Institution of Water and Environmental Management (not exactly an alarmist organisation) recently published a report entitled ‘Addicted to Plastic’ which pointed out that half of all microplastic pollution remains on land, and large amounts of microplastics removed at sewage treatment works end up back on farmland as they are spread in fertiliser ‘sludge’.

The little-reported CIWEM paper says Circular Economy measures ‘should include improved product design and substitution, extended producer responsibility and deposit return schemes’. Back to the future then.

We know that micro and nano-plastics can get into human bodies because they are sometimes put there for therapeutic purposes, such as carrying drugs.

Above: possible routes across gut to body for plastics.

Image from https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-3-319-16510-3_13.pdf

Tamara S. Galloway in book: Marine Anthropogenic Litter, Edition: 1, Chapter: Micro and nanoplastics and human health, Publisher: Springer Open, Editors: Melanie Bergmann, lars Gutow, Michael Klages, pp.343-366, July 2015?

With multiplying trillions of invisible microplastic particles circulating in our environment, getting into air, food and water, this is not a problem we can escape from. The only answer is for policy-makers to adopt a sea-change in their approach to plastics and reduce it to essential uses and those which can be guaranteed to be 100% recovered and recycled. Plastic campaigns will need to adapt too. And what of the industry ? Given what we now know, it has to be evil to continue with that beautiful strategy of reframing, deception and misdirection.

Above: small fragments of plastic ‘rubber’ from recycled tyres used in an artificial football pitch, found near a stream. Ironically Burson Marsteller (see above) also invented the “astro-turf” (fake protest) strategy.

Thank you for this brilliant piece.

If you want lawmakers world wide to pass a law that says no manufacturers can make single use plastic you will have to be able to prove that it will actually single handedly destroy life as we know it. Can you do that because that is what it is going to take?