How The Values-Politics of Eurosceptic, Climatesceptic Conservatives Halted Wind Energy in England

long post – download as a pdf

[This post follows up the previous blog ‘Brexit Values Story 2.2’ or the campaign ‘lessons of Brexit’ in values terms. For sources related to the below text see links in Full Wind Politics Timeline. See also Condensed Timeline, slides, and Political Actors].

Delabole – Britain’s first commercial wind farm (started up, 1991), Cornwall. Pic: Good Energy

This is a case study in how a ‘counter-revolution’ in values-politics set back progress in tackling a major social threat, namely climate change.

It is true that resistance from oil, coal and gas interests, business as usual momentum and feeble political commitment has been effective in stifling ‘climate progress’ on many fronts in the UK: for example continued development of oil and gas, new airport capacity and ‘offshoring’ of carbon emissions embedded in imported goods. But this case is unusual. It was a notable victory for climate sceptics in which an effective pro-climate policy was stopped, rolled back and effectively killed off.

It’s the story of how Britain or more specifically England, came to set aside its abundant resources of wind energy as a result of organized campaigning by right-wing Eurosceptic and Climatesceptic Conservative politicians. They used the threat of values-based competition between UKIP and the Tories to drive the Conservatives towards the authoritarian Settler right.

Many of the same network, certainly inspired and perhaps helped by US neocon organisations, then orchestrated the same values dog-whistles to drive the vote for Brexit in 2016.

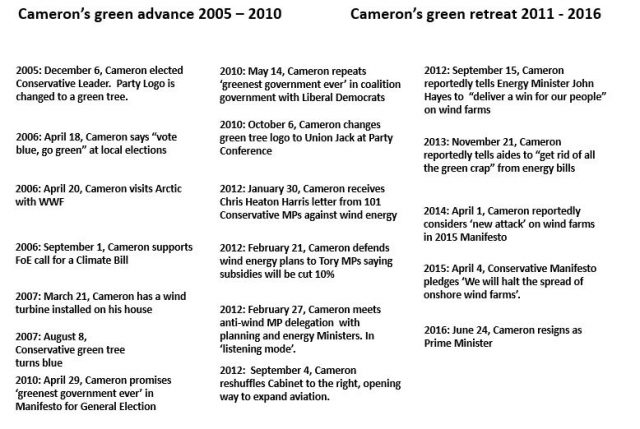

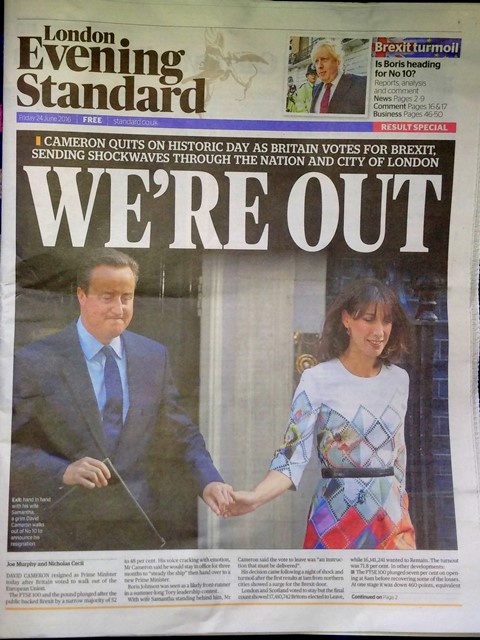

This campaign drove David Cameron and the ‘social liberalisers’ to abandon their attempt to modernize the UK Conservative Party, turning it from pro- to anti-wind.

It’s left Britain with a UKIP-style energy policy: an effective ban on its cheapest form of new renewable energy but subsidising fracking for gas. As a result the UK now faces significant problems in the struggle to decarbonize its economy. It was a significant success for climate sceptics who want to keep fossil fuel industry alive, and it happened largely below the radar of public concern.

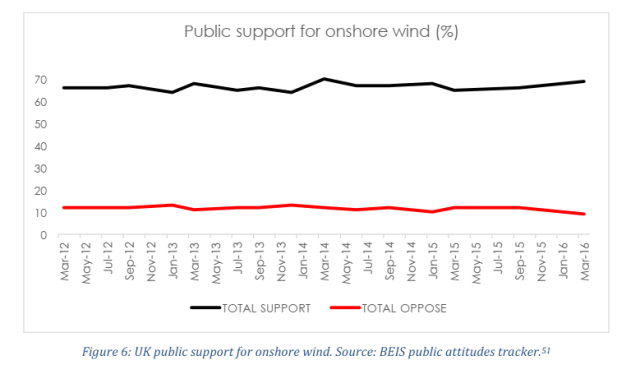

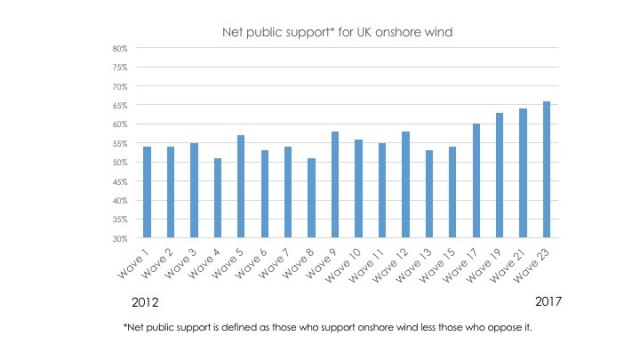

The banishment of new wind power from England came about not through any change in public opinion – it has remained overwhelmingly positive from the 2000s to date – but through a failure of environmental NGOs and the renewables industry to turn expressive support for wind into instrumental political support at a local level. In contrast, anti-wind campaigners succeeded in manipulating party politics to drive the Conservatives away from the political ‘centre’, and back towards fossil fuels. It was a struggle between the past and the future, in which the past won.

The Roots of the Political Backlash Against Wind

It could be said that former Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher instigated both sides of the fight.

On 20 September 1988 her Bruges speech warned against development of a “European Super-state”, and inspired a new generation of UK Eurosceptic Conservatives.

Just seven days later she delivered her equally famous ‘climate speech’ to the Royal Society in London, in which she warned humanity had “unwittingly begun a massive experiment with the system of this planet itself …. “a global heat trap”.

Margaret Thatcher calls for urgent action on climate change at the UN, 1989. We need “new technologies to clean up the environment” and “non-fossil fuel sources” of energy.

Thatcher’s enthusiasm for climate action lasted a few years. She redoubled her urging for international climate action in 1989, and launched the Hadley Centre into climate research before being deposed by her cabinet in a row over Europe in 1990. By then Britain had its first ‘non fossil fuel obligation’ to fund alternative energy and in 1991, its first onshore wind farm. After that, and in line with scientific findings and international agreements including EU policy, successive British governments gradually ramped up their ambitions for renewables, including onshore wind which was cheaper and easier to deploy than offshore wind.

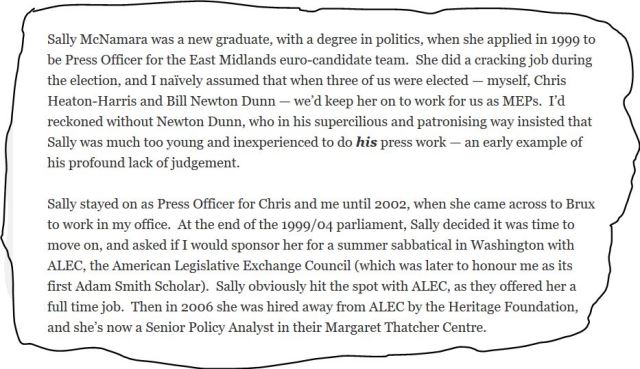

Meanwhile a cohort of mainly young Eurosceptic British Conservatives joined the European Parliament in 1999, and many set about harrying the European institutions, seeking evidence of corruption and generally criticizing and obstructing process as much as possible. They included Martin Callanan, and Daniel Hannan, Chris Heaton-Harris, and an older man, Roger Helmer who together termed themselves the ‘H-Block’.

Roger Helmer, Daniel Hannan and Chris Heaton Harris, members of the MEP ‘H Block’ in the European Parliament

Helmer and Heaton-Harris shared an office in the East Midlands where they employed Sally McNamara as a press officer. She moved with them to Brussels and went on to the US to work for the right-wing lobby group ALEC, whose conferences were subsequently attended by all four MEPs. McNamara became ALEC’s International Relations Project Director building up networks of contact between ALEC and right-wing British and European politicians, as well as being a columnist for The Bruges Group, named after Thatcher’s seminal ‘Bruges Speech’.

Sally McNamara (from Roger Helmers’ blog)

Quote from Roger Helmer’s blog in 2011 Bill Newton Dunn subsequently left the Conservatives over their drift to Euroscepticism and joined the Liberal Democrats. His son is Tom Newton Dunn, political editor of The Sun. McNamara went on to work for US defence contractor Raytheon (see also ‘Political Actors’)

Hannan had been the first director of the European Research Group in 1993, and went on to become a founder of Vote Leave, the official Leave campaign in the 2016 Referendum. Heaton-Harris later said that he was a “a bit of a greenie” when he first joined the European Parliament but became a climate sceptic after meeting Bjorn Lomborg in 2001. Helmer also credits Lomborg for his antipathy to action on climate change, and used his position in the European Parliament to host meetings of well-known professional sceptics, and even fund anti-wind energy posters in the UK.

Back in Britain all that many people knew about ‘Europe’ was the continuing civil war inside the Conservative Party which had dogged Prime Minister John Major before his defeat by pro-European Tony Blair in 1997. That and stories about rules on bent bananas created by Daily Telegraph writer Boris Johnson.

In real life, Britain was also changing. From the 1980s to the 2000s the balance of values in UK society had inverted. Settlers went from being the mainstream to the smallest values group, and the Pioneers took their place. ‘Tribal’ political alleigances were diminishing because such identity politics is an inherently Settler feature [1]. Consequently, the Pioneers and Prospectors were increasingly important in determining elections. CDSM values surveys showed that Blair appealed to many Prospectors as well as Pioneers and with the help of his deputy John Prescott, Blair’s New Labour hung onto enough of the traditional Settler vote to win two more General Elections in 2001 and 2005.

No More Nasty Party?

Reliance on a traditional authoritarian Conservative pitch appealed to the Settler base but that was shrinking and it was not enough for Michael Howard to win the 2005 General Election. So a Conservative leadership contest began, and young David Cameron entered it with a modernizing agenda, wanting the ‘detoxify’ the Conservative Party and attract more younger and female voters (Prospectors and Pioneers) on the Blair model. Cameron’s ideas were supported by Theresa May who in 2003 said that people saw the Conservatives as the “nasty party” and that, had to change.

But in Brussels the newer Eurosceptic MEPs seem to have found a political ‘madrassa’ and agitated against the old guard of pro-European Conservatives, wanting a break with the mainstream European Parliament conservative bloc the EPP.

They rallied around rightwing candidates for the leadership, such as Liam Fox. So to attract the support of the Eurosceptic wing of the party, Cameron promised that if leader, he would break with the EPP and form a new group of conservativse in the European Parliament. It proved a fateful decision, putting Cameron on a slippery slope of trying to appease the right and being pulled rigthwards. As the Europhile centrist Tory Kenneth Clarke said later, “If you want to go feeding crocodiles then you’d better not run out of buns” as if you do, they come for you.

The BBC reports Cameron’s leadership campaign success

Elected Leader in December 2005, Cameron symbolically changed the Conservative ‘torch of freedom’ logo to a green tree. He actively courted socially liberal Pioneer causes such as overseas aid, and groups like Oxfam but in 2006 he also made good on his commitment to the Eurosceptics and pulled his MEPs out of the EPP. This created a new more right-wing bloc, the ECR. Ultimately this break with the EPP would isolate Cameron from mainstream conservative leaders in the EU, undermining his attempts to win a referendum on European membership by first securing a ‘better deal’.

At home Cameron ran the local election Conservative campaign with the slogan “vote blue, go green”. To demonstrate his commitment to acting on climate change in 2006 he visited the Arctic with WWF and ‘hugged a husky’. He also pledged support to the Friends of the Earth campaign for a Climate Change Bill. By this time Cameron was pulled in two directions: one ‘progressive’ and ‘reflexive’, reinventing the Conservatives to attract Prospectors and Pioneers, the other, ‘anti-reflexive’, a rearguard action, retrenching to please ageing, increasingly right-wing party membership. The Eurosceptic outriders of the ERG hated the greenery and new softer more liberal Conservative agenda. In 2007 Cameron had a wind turbine fixed to the roof of his London house but he was under increasing pressure from the Eurosceptic right and the green tree logo went blue by August.

Cameron’s roof gets a turbine (PA)

At the 2010 General Election Cameron declared that if elected, the Conservatives would form the “greenest government ever”, although by now the tree logo had morphed into Union Jack colours.

Tory Party logos 2004, 2005, 2006, 2010 onwards

Cell-Mates Rather Than Soul-Mates

The Conservatives won the most seats of any party but failed to get a majority and went into coalition with the Liberal Democrats led by Nick Clegg. The LibDems were committed supporters of more renewable energy but their long-standing values base was a small tight section of the map, lying almost entirely in the Pioneers. As the survey below shows, it was the mirror image of the Conservative values base at the time. In government the two parties were more cell-mates than soul-mates. The coalition was an alliance of convenience rather than conviction. Although after the inconclusive result of the General Election, many saw co-operating to form some sort of government as in the broader national interest, the partnership threatened the political integrity of both partners. There was some ideological overlap between libertarian free-traders of both parties but they were atypical members. With almost no values overlap (values = deep seated attitudes and beliefs), it was an inherently unstable partnership which didn’t feel right to most of the natural supporters of either party.

Values maps of the political parties in 2012/3. There is almost no overlap between Conservative and LibDem, making the coalition feel un-natural to most supporters, and inherently fragile. But there is total overlap between UKIP and the Conservatives, making the Tories vulnerable to defections.

Values maps of the political parties in 2012/3. There is almost no overlap between Conservative and LibDem, making the coalition feel un-natural to most supporters, and inherently fragile. But there is total overlap between UKIP and the Conservatives, making the Tories vulnerable to defections.

However, the Conservatives were electorally threatened in a very direct way by the rise of UKIP, whose values base (right arrow) was entirely inside the Conservative one, and very Settler. UKIP’s share of the vote at General Elections had increased from under 1% in the 1990s to 3% in 2010, and its share of the vote at European Parliament Elections rose to 17% in 2009.

So Cameron was in a values bind. He had embraced a modernizing project to take the Conservatives into power by attracting Pioneer voters but ended up as the leader of a coalition with the Liberal Democrats. They were almost entirely Pioneers but their members mainly disliked the Conservatives, and the LibDems were in turn seen as ‘holier than thou’ and ‘do-gooders’ by many in the Settler and Golden Dreamer (Prospector) wing of his own party, who were ‘instinctively’ climate sceptic and preferred UKIPs ideas to those of the LibDems.

Climate scepticism came easily to the socially-conservative Settler motivational values group as it is pre-disposed to avoid change and signs of change, whether to the landscape or to culture (eg immigration). As a result, across the world, Settlers are at the epicentre of climate scepticism where it exists, and invariably the last to support new behaviours, ideas or technologies. As it happens, although they are only 25% of the population (and 30% of the electorate), the UK has a larger proportion of Settlers than almost any other country.

The overlapping values base of UKIP and the Conservatives meant both were competing for the support of the most instinctively climate sceptic people in the UK (below). Which meant the seemingly esoteric issue of wind technology could be a live electoral issue in Tory-UKIP competition.

This climate scepticism also coincided with anti-immigration sentiment – agreement with “there are too many foreigners in my country” – and, as seen earlier (Brexit Values Story parts 1, 2.1 and 2.2), disapproval of the EU. So although UKIP’s three main policy planks – anti-EU, anti-immigration and anti-wind – were often seen as limited and eccentric by more mainstream politicians in the early 2000s (Cameron called UKIP ‘fruitcakes’), they made perfect sense as a values platform with which to peel away support from the Conservatives.

In January 2006 David Hanley of the University of Cardiff wrote in Politico that ‘Tories of all shades remain very frightened of UKIP, especially younger candidates who have confronted it and had to explain why Tory policy on Europe is less red-blooded’.

Luff’s Bill

In 2009 Conservative MP Peter Luff proposed a wind farm (habitation) bill, to keep larger wind turbines 1.5 miles away from houses. Luff said he was not a climate sceptic but pointed out (rightly) that rules for compensating local householders and planning restrictions were both more robust in other countries than in England and Wales. He had been contacted by “extraordinary” numbers of people from around England, concerned about large wind turbines that were going to be put up near their homes.

Luff’s bill was introduced under the ’10 Minute Rule’ and got nowhere but it created a template for policy opposition, and help was on the way.

Chris Heaton-Harris began campaigning against wind farms as early as 2008, at Brixworth in Northants, while he was still a MEP rather than a MP.

From the Brixworth Bulletin in 2008 The author seems sceptical that the meeting had in fact been organised by local parish councils

When elected in 2010, Heaton Harris used his maiden speech to attack the “folly” of wind farms and reintroduced Luff’s Bill as a ‘proximity’ Bill. That too failed but when in 2010 the government tried to rationalise planning rules in a NPPF or National Planning Policy Framework, anti-wind campaigns were gifted a way to make their cause part of a national issue and to align with established groups such as the CPRE (Council for the Protection of Rural England).

By 2011 a raft of larger countryside groups were opposing the NPPF and the Daily Telegraph had started a ‘Hands off Our Land’ campaign. Heaton-Harris pointed out that the NPPF contained a ‘presumption for sustainable development’, which he said meant a presumption in favour of wind farms.

Heaton Harris’s book on Kelmarsh and a UKIP guide to fighting wind farms, both published in 2012

In early 2012, prompted by an Inspectors decision in favour of the Kelmarsh wind farm despite opposition of local councils, Heaton-Harris, who was Chair of the ERG from 2010 to 2016, invited all Conservative MPs to a meeting. On January 30, 101 of them and a few other MPs signed a letter to David Cameron. It demanded a ‘dramatic’ cut in funding for onshore wind, and a rewriting of the planning rules so that ‘local communities’ could easily stop wind farms.

A meeting with Cameron and his energy and planning Ministers soon followed, and the Conservative pro-wind policy started to be dismantled. It began the slow death of Cameron’s seven year experiment in greening the Tory Party and his attempt to steer the Conservatives into Prospector-Pioneer territory. In 2015 the Conservative manifesto would announce that ‘we will halt the spread of onshore wind farms’.

By March 2012 it was reported that local opposition to windfarms had tripled since 2010 following political and media attacks focused on landscape impacts and subsidy, even though most people still supported having wind farms nearby.

By April 2012 Chris Heaton Harris was announcing “the beginning of the end” of onshore wind, and in June Lincolnshire County Council adopted a policy of not approving wind farms within 10km of any village, effectively excluding new wind from the county. In October that year Heaton Harris launched a lobbying company ‘Together Against Wind’ to coordinate and raise funds for a national network of local campaigns to pressure Ministers.

The Together Against Wind campaign run (2012 – 17) by Chris Heaton Harris and later his protégé Thomas Pursglove MP – from the internet archive. It was most active in 2012. See also Political Actors doc.

Acute versus Diffuse

While public opinion remained overwhelmingly pro-wind, strong opposition to wind was concentrated in a small segment of older right-wing voters likely to vote for UKIP or the Tories. Yet only a handful of activists were needed to manifest local ‘community’ opposition, and to populate a photo for the local press or a Facebook post.

Roger Helmer MEP and Chris Heaton-Harris MP in 2013 meeting with REVOLT campaigners in Lincolnshire

It is possible that the anti-wind campaign recruited some supporters from the ‘Countryside Marches’ co-ordinated by the pro-hunting group Countryside Alliance in the 2000s. In a Values and Voters Study (2005) I wrote

‘The Countryside Alliance and its campaign for ‘rural values’ and foxhunting, pitted a Settler-dominated group against a largely disinterested and mostly esteem-driven ‘urban majority’. (Although in London, over 40% of the population is made up of inner-directed Pioneers). At first their numbers panicked Ministers but it soon became apparent that demographics were against them: they represented a highly mobilised but tiny group of people, and for all their huffing and puffing, were natural followers rather than activists. In a war they would have been natural soldiers but in a political campaign their traditional conservatism and inability to make common cause with other groups in society, worked against them.’

The Alliance held ‘marches on London’ which reached 300,000 (2002) but as these went on it showed their real base was limited. The anti-wind campaign did not make this mistake: it organized a top down co-ordination of protest populated with ‘community’ actors. It focused on organising and pressuring MPs locally, where its numbers seemed big enough, and on letter writing to Ministers who were in any case already being briefed to respond to their demands. It then aligned with other established organizations on a case by case basis.

Since 2011 Heaton-Harris had been publishing a guide ‘Fighting Wind Farms’ and offering to help local campaigners around the country. The anti-wind movement set about organizing constituency by constituency support to local groups, while the mainstream environmental movement mainly remained focused on national and international climate policy. The anti-wind campaign had the upper hand as it mobilized a small number of very motivated people who could exert acute pressure on a very sensitive target (Conservative electoral fears), whereas the pro-wind lobby was vast but its effect was very diffuse.

Like Major before him, Cameron was now dogged by Eurosceptic insurrections. In October 2011 he suffered the biggest ‘biggest ever’ rebellion by Tory MPs over whether there would be a referendum on Europe and only avoided defeat through support from the Opposition. LSE political Blogger Pete Radford wrote that Cameron had ‘little room to manoeuvre’ and the right were ‘picking apart his liberal conservative project’. Of the 81 Conservative rebels, ‘a massive 49 were new MPs, elected in 2010’ and, noted Radford: ‘the party is no longer split between sceptics and non-sceptics but … hard sceptics and soft sceptics’. Since May 2010, there had already been ‘22 Conservative rebellions over Europe’.

A Systematic Shut Down

Over the three years following the 2012 Heaton-Harris letter, Cameron’s Ministers conducted a systematic shut-down of the onshore wind industry, which continued from 2016 under Theresa May.

First the industry was demonized and existing funding was wound back. Then planning rules were turned upside down to create a presumption against onshore wind, making wind farms almost impossible to build.

To achieve these ends, the Conservatives overcame opposition from their junior coalition partners, the Liberal Democrats. Anti-wind politicians were installed to deliver the change, such as Conservative Energy Minister John Hayes who Cameron asked to “deliver a win for our people” on wind farms.

Eric Pickles – as planning Minister, called in and cancelled many wind farms

Local Government Minister Eric Pickles was deployed to put the brakes on wind projects already in ‘the pipeline’. In 2013 he revised planning rules to give more weight to local concerns about landscape and ‘heritage’, and by March 2014 had intervened to take 35 wind farm planning appeals away from inspectors. He took extra powers to intervene and extended them until the 2015 election, and by November 2014 he had halted 50 wind farms. This, it was said, at the cost of £500m and 2000 rural jobs. At least one wind farm was stopped despite having local Council support.

2014 – Pickles kills off Killington wind farm despite community and Council support

A new financial ‘framework’ was introduced, ostensibly to protect consumers from higher energy bills but in practice it was used to cut funds for renewables while subsidies for oil and fracking were increased.

Finally, when the rapidly falling cost of new onshore wind and largescale solar-pv meant they became by far the most cost-effective way to generate electricity, and so would have beaten bids using coal, oil, gas or nuclear in the Contracts for a Difference auctions, large onshore wind and solar were excluded from the government-controlled energy marketplace when the government simply did not hold the relevant auctions.

While this process wasn’t exactly secret (see the large number of media reports cited in the Timelines), it was stealthy and obscure, involving gradual adjustment to technical orders way below the radar of popular attention. The mainstream media mainly covered the issue through individual site conflicts with a particular angle of interest (eg at Naseby Battlefield in Northants or at Big Field in Cornwall where it divided the Church of England and its sustainability policy from some parishioners). Changes to energy policy often explained through personality conflicts within the coalition government (2010-15), such as when pro-renewables Ministers like Ed Davey or Greg Barker were replaced or stood down. In the classic manner of a government u-turn, the throttling, starving and eventual exclusion of onshore wind avoided any dramatic moment of decision that might create an opportunity to critics.

A 2014 story from The Guardian about a long running battle to win approval for Good Energy’s ‘Big Field’ wind farm in Cornwall which divided a community (and split the church), and led some people to say they would switch from voting Conservative or LibDem to UKIP (it was ultimately rejected).

The natural proponents of wind were the renewables industry and the green NGOs but the task of organizing a meaningful defence seemed to fall between them. The wind industry itself relied on a legalistic approach and proved generally inept at mobilizing public support, in some cases becoming its own worst enemy. The wind-delivery system was high handed and remote, designed to be backed by top-down central government policy, not to have to win support bottom-up against local opposition.

Divided ‘Greens’

The environmental NGOs failed to organize constituency-level campaigns for wind, perhaps partly because they had relatively little engagement with Conservative voters, and perhaps in part because it was assumed that the provisions of their great achievement, the Climate Change Act, would ensure energy policy kept moving in the ‘right direction’. The NGOs secured sustained cross party backing on climate policy (with the exception of UKIP) but not on energy policy.

The NGOs were also split, with local CPRE groups and sometimes the National Trust and Wildlife Trusts taking an active role in opposing wind farms, which in practice helped fuel and legitimize the Heaton-Harris campaign.

Most active NGO engagement focused on the readily achievable, such as promoting school or community renewables projects, or on advocacy of policy arguments rather than organizing. There was for example, no demonstration of the scale of the wind or solar industry in terms of jobs, such as by bringing workers together when it was still a burgeoning business. The wind industry and the green NGOs never turned overwhelmingly favourable public opinion into an effective lobby. In contrast, although the anti-wind lobby represented just a tiny sliver of public opinion, when their activism was inserted into the machinery organised by Heaton Harris and his fellow travelers, it exerted enormous political leverage.

From Blown Away by the ECIU, 2017

‘Green Crap’, ‘Green Taliban’, ‘Green Blob’

If a British government is hell-bent on pushing through a policy and using its many opportunities to propagandize to support it, then unless there is some telling moment of conflict for opposition to rally around, it is almost impossible for civil society to withstand it.

In 2010 the Conservative Manifesto Conservative manifesto promised to ‘unleash the power of green enterprise and promote resource efficiency to generate thousands of green jobs’. It spoke of ‘our responsibility to be the greenest government in our history’. Its vision is for Britain was to be ‘the world’s first low-carbon economy’. All that went out the window as the Tories aped UKIP.

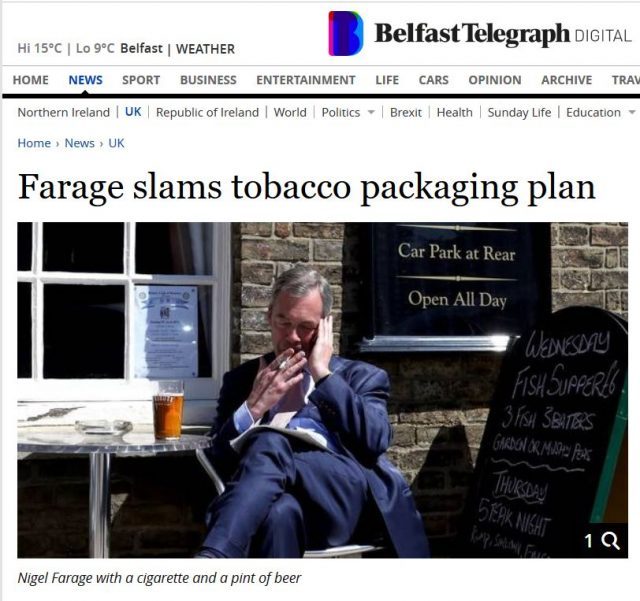

With a political strategy of trying to out-UKIP-UKIP, Conservative Ministers did little to challenge the barrage of anti-environmental propaganda emanating from Nigel Farage, who for example wildly exaggerated the size of wind subsidies (six fold). The new narrative about onshore wind held that at best, it was a necessary evil, and invariably an imposition on communities and a burden on electricity bill payers.

George Osborne used the 2011 Conservative Conference to denounce green regulation

In 2011 amidst widespread criticism of ‘austerity’, Chancellor George Osborne singled out “a decade of environmental laws and regulations” for “piling costs on the energy bills of households and companies”. In 2012 Osborne took to calling green industries, environmental NGOs and government energy officials the “green Taliban”. In 2013 Cameron told aides to “get rid of all the green crap” from energy bills. Rather than fighting climate change by creating the world’s first low-carbon economy, investment in renewable energy was framed as a danger to be controlled. Osborne had a ‘Levy Control Framework’ set up. Opposing onshore wind farms became the poster-child for a more general abandonment of environmental ambition. In 2014 Owen Patterson declared he was proud to have fought against environmental NGOs as Environment Secretary, denouncing them as the “green blob”.

On losing his job at DEFRA Owen Patterson MP denounced the “green blob” and then delivered a talk promoting fracking at the climate-sceptic front group the GWPF

Following Cameron’s capitulation to Heaton-Harris’s 101 Tories in 2012, Ministers adopted the framing of communities as victims of wind energy. John Hayes, who Peter Lilley found “on my side” and “useful” at the Department of Energy, announced “we can no longer have wind turbines imposed on communities”. In 2014 Energy Minister Michael Fallon promised that if the Conservatives were elected in 2015, “changes to planning rules will … give communities more power to reject onshore wind”. In 2015 Kris Hopkins, a Conservative communities minister, said wind turbines could be “a blight on the landscape, harming the local environment and damaging heritage for miles around”.

The message was clear: the Conservatives were no longer on the green side but on the side of those who climate-sceptic journalist James Delingpole described as Shire Tories (or those aspiring to be) who believed ‘their country home … is their castle’ and did not expect ‘to have their peace disturbed’, or ‘their views ruined’.

‘UKIP Can Deny Us A Majority With 5%’

On the other hand, to extract political benefits, the government still had to signal the political logic to its own followers. Most of this can be found in conservative blogs and comment pieces in conservative newspapers citing ‘sources’. For example in May 2012, the creator of ConservativeHome website Tim Montgomerie, who had previously explained the electoral benefits of Cameron’s green repositioning, warned: “UKIP doesn’t need to get 10% to cause us damage. A 5% or 6% vote share will be enough to stop us winning many of the marginal seats that are necessary for a Conservative majority”.

The next month Benedict Brogan of the Daily Telegraph wrote that George Osborne would throw ‘red meat’ to party members and use finance to ‘kill’ onshore wind ‘stone dead’.

The Guardian reports a Greenpeace sting video in which Chris Heaton Harris explains how he arranged for an ‘anti wind’ candidate to stand in the 2012 Corby by-election, and “there’s a bit of strategy behind what’s going on”.

Other Conservatives were prepared to tolerate support for UKIP so long the overall effect was to make the party more Euro- and Climate-sceptic, and anti-wind. At the Corby by-election Heaton Harris was caught on camera by Greenpeace saying he “didn’t give a toss” if the ‘anti-wind candidate’ James Delingpole (who Heaton-Harris had helped to stand despite himself being the official manager of the Conservative campaign), was to endorse UKIP. He simply wanted to get opposition to wind energy “written into the DNA” of the Tory Party. His fellow East Midlands Conservative MP, arch Euro-sceptic Peter Bone, wrote in 2014 that UKIP was a ‘good thing’ because it would pull the Conservatives back to the right.

Bone, Farage and (right) Pursglove in Northamptonshire for the launch of GO Movement (Grassroots Out) a pro Brexit group, in 2016. Bone and Pursglove both spoke at the UKIP Conference despite being Conservative MPs. Photo from Northampton Chronicle

Enough Wind Already

Many reports had it that Osborne and his Treasury team were pro-gas including fracking, and it suited them to divert financial support to the fossil fuel gas rather than wind. At least in the short term, the growing public dislike of fracking was simply ignored, and once fracking development began, it was mainly in Labour not Conservative constituencies.

To maintain some claim to no longer be the ‘nasty’ party, Osborne ring-fenced funding for the NHS but sacrificed greenery. Private polling may well have indicated that this was a bulwark against loss of Conservative votes to Labour, which was more important than any loss to the LibDems or Greens.

An awkward obstacle remained the statutory carbon budget system set up through the Climate Change Act which had become law in 2008 under the Climate Change Committee. The clear logic of this is to reduce Britain’s carbon emissions and progressively decarbonize the economy. But so long as the government could show overall emissions were falling (which they did, mainly because the final tranche of coal power stations was being closed down) the government could claim its climate policy was succeeding.

As well as overall emission targets and carbon budgets, the government had energy plans with targets and obscure sub-targets for proportions of power to be generated by renewables. Chris Heaton Harris used these to frame onshore wind as having already received ‘too much’ funding. Then by focusing on the short not even the medium term, the government used this to justify withdrawing “subsidies”: it found a way to claim that there was already ‘enough wind’. The reference target was 2020, and an end to finance was brought forward a year to 2016.

Political Consequences

Cameron and Osborne dropped wind energy in a short term bid to see off the Eurosceptic Tory right. In the end it failed because the same lobby also forced them into an EU referendum which they lost.

Chris Heaton Harris became a government whip under Theresa May and then in 2018 a Minister in the Department for Exiting the European Union (DEXU) responsible for preparing for a no-deal Brexit, until he resigned on 3 April 2019 over a delay to Brexit. Last year he caused outrage in Universities when he wrote asking for the names and notes of academics lecturing on Brexit. According to his constituency website he is still campaigning against wind and offering to help local campaigners object to wind farms.

Voices That Were Not Heard

Since Cameron’s volte face became apparent in 2012, the wind industry, carbon finance and risk experts, NGOs, the Climate Change Committee and Parliamentary committees have repeatedly criticised the government for stifling onshore wind just as it has become the cheapest form of new energy. They point to an opportunity cost: onshore wind offers huge economic and climate benefits, and lots of skilled jobs. But finance for renewables projects and the wind-construction industry itself is highly mobile, so when there are more favourable opportunities elsewhere, the investment simply moves and its voice is no longer heard.

The larger wind companies are also invested in offshore wind, complicating their relationship with government which has been able to point to significant increases in offshore generation as a success story. Plus although community energy schemes have been a victim of the jihad against wind, nearly all of Britain’s onshore wind has been delivered by large companies. The paucity of community owned schemes (common in countries like Denmark) also meant that there were few community level voices raised to express support for wind when the campaign began.

Stirrings Of A Rethink

When Osborne and Cameron backed a reversal of policy on wind, Osborne in particular promoted fracking as an energy alternative. Quite aside from the obvious contradiction between a new dash-for-gas and climate policy, and the likely unpopularity of fracking locally, from the start, geologists had warned that the UK’s frackable gas resources were not comparable with those in the US. They expressed doubts about the viability of the putative UK fracking industry.

By 2018 Cabinet Office documents unearthed by Greenpeace showed that whereas the shale gas industry had anticipated 4,000 horizontal wells by 2032, government projections now put the figure at just 155 by 2025. For several years opposition by environment groups and local communities delayed any commercial fracking. (In April 2019 INEOS and Quadrilla, the only firms to actually try fracking for gas in the UK, were lobbying for relaxations of earthquake rules, with INEOS saying it might pull out altogether).

Yet over the same time period of 2012 to 2019, costs of new onshore wind generation fell dramatically. It was not surprising that this happened as the technology matured. It had been predicted and the falling cost of onshore wind and solar pv was, after all, one reason the government was already considering a cut in ‘subsidies’ in 2012.

Even so, Together Against Wind was claiming in 2014 that ‘new forms’ of generation would cost twice as much as coal or nuclear (at £50/MWHr). By 2017 Arup said new onshore wind would be as cheap as gas and half the cost of nuclear at Hinkley. The subsidy requirement for offshore wind, which was still allowed to compete in auctions, fell by 50% between 2015 and 2017. In 2017, Cornwall Energy put the cost of new onshore wind at £40/MWH, others at £46/MWH, both less than new gas. In 2018 the Climate Change Committee urged the government to use “simple, low-cost” options such as onshore wind and efficiency to cut emissions in the 2020s. Ostensibly, it has always remained government policy to de-carbonize at ‘least cost’.

No doubt this prompted some in Whitehall to argue for policy on wind energy to be ‘revised’, although by now a lot of investor interest has been lost. In 2016 ENDS reported that the UK had dropped to an all-time low of 14th place in Ernst and Young’s ranking of country attractiveness for renewable energy Investment (behind Morocco, Brazil, Mexico and others). In 2018 the Parliamentary Environmental Audit Committee called the fall in renewables investment “dramatic and worrying” and questioned the UK’s ability to meet its legally-binding carbon reduction targets.

Even in the Conservative Party, voices have once again been raised in support of onshore wind. In 2017 Sam Hall from Bright Blue wrote at Conservative Home: ‘Polling shows ‘70 per cent of Conservatives are concerned about the impacts of climate change’ and ‘Conservatives have a more positive view of renewable energy forms like solar, tidal, offshore and onshore wind, and biomass, than they do of nuclear and fossil fuels. Even more remarkably, new onshore wind developments, which the last Conservative manifesto pledged to halt, are supported by a majority (59 per cent) of Conservatives, provided they did not receive any subsidy’. Also in 2017, Simon Clarke, Conservative MP for Middlesbrough South and East Cleveland wrote an article at Conservative Home: ‘The case for lifting the national bar on onshore wind’.

It seems that like Europe, wind energy is a political football within the Conservative Party, and is being kicked about by the same two sides. In 2018 the Daily Telegraph reported that the row over onshore wind ‘threatens to re-ignite’ within the Tory party after ‘energy ministers Claire Perry and Richard Harrington alarmed their backbench colleagues by revealing that they are working on ways to support future projects.’

Some Tories open to onshore wind: Claire Perry MP, Richard Harrington MP, Sam Hall of Bright Blue and Simon Clarke MP

In 2018 Business and Energy secretary Greg Clark announced that the “energy trilemma” was “coming to an end”. Cheap power, ‘ he said “is now green power”. Zero subsidy say Clark should be a principle, and “it is looking now possible, indeed likely, that by the mid 2020s, green power will be the cheapest power. It can be zero subsidy”.

It would probably be wrong however to imagine that the Civil Service is wholly impartial or united on this topic, or that economic and ecological rationality outweighs values judgements or ideology in Westminster, and therefore onshore wind power is now certain to be re-started.

For one thing, a decade of sustained anti-wind propaganda has left a mental footprint in the perceptions of MPs. A July 2018 YouGov found just 8% of them knew that onshore wind farms are now the cheapest new source of electrical generation. 12% thought it was nuclear. They also overestimated opposition to onshore wind. The latest government survey showed just 2% strongly oppose onshore wind but only 9% of MPs believed the figure to be less than 5%. Most guessed that ‘strong opposition’ was above 20%.

Source: Energy and Climate Change Public Attitudes Tracker, BEIS – from Chris Goodall’s blog

Source: Energy and Climate Change Public Attitudes Tracker, BEIS from Chris Goodall’s blog

In 2017 a detailed analysis of the long-running government tracker poll on wind by Chris Goodall, blogger at ‘Carbon Commentary’ revealed that ‘just 1 person between 16 and 44 from the entire interview panel [of 2000] was ‘strongly opposed’ to wind’. Goodall wrote: ‘Across all age ranges, wind seems to be rising in popularity. The only group with more than a few opponents are those over 65. And yet the reduction in those opposing onshore wind has been fastest in this age range. Media coverage shouldn’t start from the assumption that people don’t like turbines. Wind power is popular. Vastly more popular than fracking’.

I’m told that confronted with this evidence and even the fact that onshore wind is more popular in rural than urban areas, a senior Conservative MP just flatly refused to believe it as it did not reflect his postbag. The obvious explanation is an effective and well organized campaign of a very few people made to appear like a lot.

In autumn 2018 energy blogger Professor David Toke asserted that the Treasury still aimed to change policy so that ‘almost all future development for renewable energy in the UK will be stopped. Continued incentives and tax breaks for nuclear power, shale gas and conventional power stations will, however, remain in place.’ It wanted to end Contracts for a Difference (CfDs), end ‘all incentives to solar pv, including for solar power exported to the electricity distribution system’, and ‘the carbon price floor which makes fossil fuel more expensive and non-fossil sources relatively cheaper’. The war is far from over and as things stand, the anti-wind lobby is winning.

Enemies of Science and Regulation

Matt Reed’s blog investigating UKIP and wind

‘Reflexivity’ and ‘reflexive modernity’ is an esoteric idea but an important part of it is that society reinvents itself and its systems by acting on scientific advances in understanding. As Matt Reed wrote in a 2016 blog, UKIP’s online propaganda activity on wind farms it is part of an anti-reflexive backlash or counter-revolution, in which scientific knowledge and understanding is rejected. This is why it aligns with same psychological, political and ideological divide as, for example, climate scepticism and rejection of scientific evidence about the dangers of smoking. He quotes Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway, in their book (and film) Merchants of Doubt, How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming: “the enemies of government regulation of the marketplace became the enemies of science”.

From Roger Helmer’s blog

Farage doing a bit of values signalling (the packaging refers to health warnings)

So the staying of wind in England is very much about an interruption of modernity and a sacrifice of the public interest in favour of those private interests with a vested interest in perpetuating the profitable conditions of the past. Which is why it is not surprising that rejection of the seemingly apolitical option of onshore wind power became a symbol in the service of ‘Euroscepticism’, and a way to actualize a dream of how some would like the world to be (we don’t need renewable energy), rather than how it needs to be (actually we do).

Conspiracy Footnote

There was obviously a co-ordinated campaign by ERG members and other Conservative right-wingers to get the Cameron government to drop wind, and then a campaign by many of the same MPs, in collusion with Ministers, to dismantle the onshore wind industry in England. This seems to have involved Tory right-wingers well beyond Heaton Harris, such as Peter Lilley.

But was there a conspiracy or an organised effort with foreign influence behind the killing of the wind in England? I don’t know. More like a convergence of interests perhaps.

Reed suggests that opportunism rather than strategy explains the largely imaginary mobilization of a ‘rural vote’ by UKIP but the line between opportunism and planned action, is a rather grey one, as has been the line between UKIP and the right wing of the Tory Party.

It is true that there is a trail of breadcrumbs which certainly show connections. The political bonds between players such as ALEC in the US who Heaton Harris asked for help from in his political project and who responded positively (what the help was, we don’t know), and Bjorn Lomborg and his fellow Eurosceptics like Liam Fox and Roger Helmer and Daniel Hanahan are real enough. As were theirs also to the US right-wing. As are the links between the climate sceptics of Tufton Street in London and the US right-wing funders, and those from them to the fossil fuel industry (sometimes one and the same). NGOs like Desmog and journalists like George Monbiot have spent a much longer time looking into the Eurosceptic-Climatesceptic ecosystem.

As to Heaton Harris’s links to Trump whom he hoped would speak at an ill-fated fundraiser for his campaign front ‘Together Against Wind’ back in 2012, was that imaginary or real? Trump, he told putative donors, was one of his ‘biggest supporters’.

One of my ‘biggest supporters’ wrote Heaton Harris in a mailer for an anti-wind fundraiser

At the other extreme perhaps, it may be just a coincidence of values, the politics of property interests, and the unintended side effects of the NPPF, which brought together groups like the CPRE and the Eurosceptic-Climatesceptic right-wing, through figures such as David Montagu-Smith. He was Chairman of West Northamptonshire CPRE and is and was Chairman of Rathlin Energy, an oil and gas firm involved in fracking.

David Montagu Smith of CPRE and Rathlin Energy (from a Protect Our North Coast video)

Protect Our North Coast opposed fracking development by Rathlin in Northern Ireland

Others don’t think it is coincidence, for instance Renewable energy consultant Alison Fogg. She wrote at Spin Watch about her experiences of anti-wind campaigning in the South West in ‘Connecting The Dots: A Firsthand Account Of How The UKIP Surge Drove The Tories To Sabotage The Renewables Industry’. That describes how in 2014 she found that it was almost impossible to get positive press coverage in the local North Devon Journal because of links between UKIP, the “Slay The Array” campaign against an offshore wind farm, and the local branch of the CPRE, whose chair, Penny Evans, had stood for UKIP. She recalls that: ‘At one Slay the Array meeting, a 59-year-old supporter of the Array plans was ejected after asking too many questions. This man was then beaten up. And that was at a renewable energy event’. The main suspect ‘was described by police as “wearing a purple jacket with a UKIP badge”’.

The US right-wing still funds anti-renewables campaigns and the authoritarian anti-modern British right – such as the ERG and UKIP – which so successfully inflamed Settler reflexes, has links to its American cousins. They share a joint dislike of the ‘progressive’ public interest politics of the EU, making them bedfellows over Brexit. It is their attitudes and beliefs rather than that of the people of England who have so far won out in determining energy policy.

View a timeline in slides:

ends

[1] ‘Security-driven’ with an unmet need for safety, security and identity. As a result they are cautious and change-averse (change being a risk), and seek certainty, leading them to generally conclude that things should be left as they are, or preferably returned to the past, the ‘good old days’. Settlers desire to be ‘normal’ and are pained by change if it redefines normal and requires them to change in order to stay ‘normal’. This social conservatism has always predisposed Settlers to resist or avoid new technologies as long as possible, to uphold tradition and to seek out reassurance in terms of continuity, from recreations and food to manners and social signals in general that cultural continuity is being conserved.

This makes Settlers ‘naturally’ averse to obvious new changes such as large white wind turbines appearing in their local landscape. Later once these are normal, Settlers may become guardians of the new normal – exactly this happened with old style windmills, originally opposed as foreign intrusions, now treasured heritage.

Many Settlers also have a strong sense of local identity and resist changes to it, whether rapid cultural change in the shape of visibly different immigrants, or new developments that make a place ‘unrecognizable’.

This is really sloppy analysis. We don’t need a conspiracy of oil interests no doubt funded by the Koch brothers to explain why this campaign is successful. In case you hadn’t noticed, England, after Malta is the most densely populated country in Europe and one with a 200 year old tradition of trying to protect our green and pleasant land from industrial despoliation. All the campaign did was tap into that.

What is your alternative? I live within sight of the Quantock and N

Blackdown Hill’s. Both perfect for onshore wind. I also live fifteen miles from Hinckley Point. In its shadow you might say. To deliver the power from Hinckley Point would require 1,000 plus wind turbines. Give me Hinckley Point every day even if it’s twice the price.

Even James Loveluck thought wind turbines on land were an aberration.