Chris Rose, 11 November 2025 download as pdf

From the New York Times

Following last week’s backlash against Donald Trump’s administration expressed in public votes across a diverse range of States, media and no doubt Democratic political attention focused on what it means for electoral strategy going into the 2026 Mid-Terms and the 2028 national US election. But with the consequences of Trump’s divisive policies all too evident at home and abroad, now could also be a good time for political thinkers in the US to look at a different question: what can they do to reduce political polarization?

Right now there must be a huge temptation for Democrats not to think about it. If the pendulum swings against the Republicans it might not, Electoral College aside, take a huge shift in national political sentiment to return a Democratic President – Trump beat Harris by only 49.8% to 48.3%. Polls in New Jersey and Virginia found that previous Trump supporters switching to Democrats Mikie Sherrill and Abigail Spanberger played a bigger role last Tuesday than turnout effects. Almost all politicians decry the effects of polarization but they may be inclined to forget about it when it works to their benefit.

A similar but different situation exists in the UK. Keir Starmer won a large majority of seats – 411 giving a majority of 174 – but his vote share was just ‘33.7%, the lowest of any majority party on record, making this the least proportional general election in British history’. He’s

Like many European countries, politics in Britain is destabilising, old affinities are no longer predictors of voter behaviour, and particularly in the last decade (in the EU and UK, stimulated by Brexit), political scientists and a trickle of politicians, eventually followed by mainstream pollsters, political journalists and commentators, have started to say that something else is driving reconfiguration of the modern political landscape, something not well explained in terms of the old Left-Right ideology.

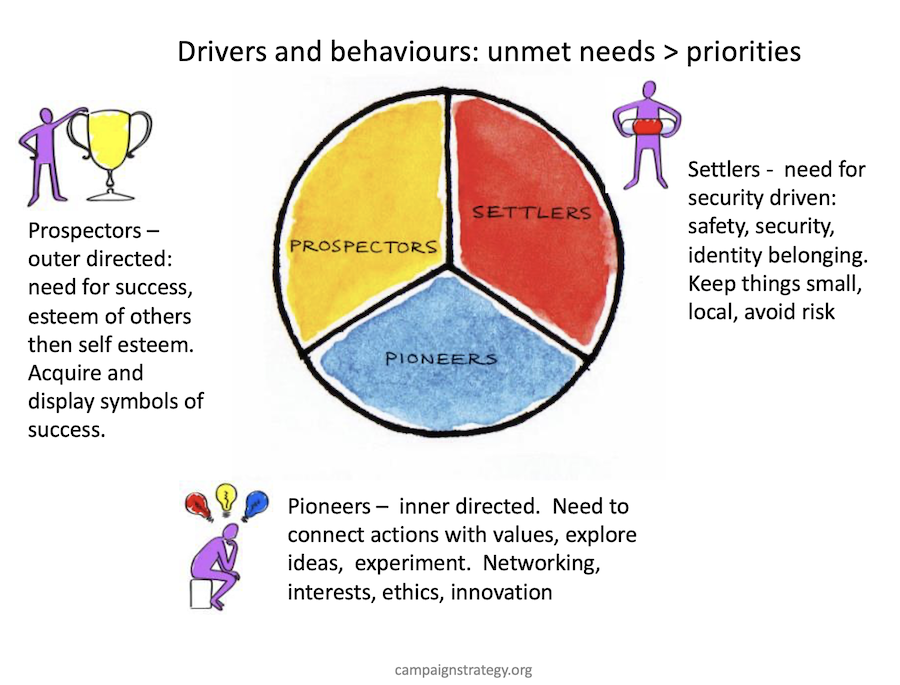

Many agree that ‘something’ is values divides, although few politicians have the knowledge to understand it or the language to describe it. For the last year or two I’ve been researching values and political polarization. There is no shortage of material, although little of it explains more than a sliver of the processes involved. The most obvious role of politicians in deliberate polarization is using ‘cultural issue dog whistles’ as ‘wedges’ to divide, or corral an audience. Some of the more structural factors in which policies and electoral strategies have played a less obvious role include:

- Alienation from politics and non-voting amongst people who felt mainstream parties were not listening to their concerns (such as immigration, loss of community and continuity through deindustrialisation/ globalisation) while they were attending to ‘progressive’ concerns such as gender rights, cancel culture, and environmentalism (becoming political correctness = ‘wokery’ – see Brexit Split slides 28 – 33, and PCness inBrexit Warning)

- Slow but sure and long-term reduction in real economic prospects of those who relied on wages rather than an increase in asset value, which increased under both left and right ‘neoliberal’ mainstream governments, leading to disillusionment and despair amongst a minority but sizeable economic underclass/ precariat, and a large part of the first group above (in UK and EU probably about a third of the population and increasingly including university-educated young).

- Transfer of significant economic decision making to institutions (eg Central Banks) taking alternative policy options – such as reversing the asset divide – off the agenda at elections (depoliticization of economics, financialization, representation deficit)

- Decades in which post-industrial (service/ knowledge) opportunities went disproportionately to the educated, who also became more able to meet their needs for safety, security and belonging (in CDSM Maslowian terms Settlers), and then Prospector needs (seeking esteem of others and then self-esteem), becoming Pioneers (now the core vote for example of the UK Labour Party), most of them ‘progressives’. (L/R divides> values divides & a University education/not divide, identified by pollsters)

- The increasing domination of political parties (candidate selection etc) and so legislatures, by a highly educated Pioneer-weighted class (eg in the US, UK, Germany)

- Re-engagement in politics by the disengaged when new entrants, mainly called right-wing parties but perhaps better termed ‘antisystem’ parties, attacked ‘progressive’ politically correct policies and immigration (as in the UK Brexit Referendum and Trump’s first election but starting in the 1990s)

- The enabling of communication and organisation by such anti-system parties via Social Media, which Christian Welzel of the World Values Survey suggested at a 2024 conference, ‘dramatically … broke the traditional gatekeeping and agenda-setting monopolies and now, new actors have access to the political arena and can mobilise these [previously] frustrated non-voters’. Welzel and others have found a lack of polarization between supporters of mainstream European parties 1990s – 2020s but a split between those and populist parties in terms of trust in conventional politics.

- The well-documented gradual loss of audience for mediated-media (eg newspapers), particularly locally, the fracturing of truly-mass-media TV by narrowcast cable TV by 2000, and from 2005 audience creep to unmediated unregulated Social Media, and since 2023, AI information pollution, facilitating social and values bubbling and silo-isation with reaffirmation of untested perceptions, and spread of conspiracy theories, all reducing trust and potentiating polarization.

Such factors created new inequalities, lines of conflict and resentments which could not be easily articulated in old-school political terms of left and right, and which do not fit the templates of most conventional governing parties – agenda, process, priorities, culture, assumptions. With most politicians* and political journalists often struggling to articulate this phenomenon and persisting with Left-Right terminology, the social and psychological (values) dynamics alive in the electorate are often untethered from conventional political offers.

(* For an example of a politician who did understand and use a values analysis in electoral politics see this post about Jon Cruddas MP and a UK General Election).

Some Things Politicians Might Do About Polarization

Some mitigations are at least partly under the control of politicians and parties, and more once they are in government. How politics is done, the offer of parties – at elections – the retail offer, what’s included or not, the delivery in government, leading to who feels pleased, disappointed, neglected or not, and whether governing style increases or decreases polarization during an administration. For example:

Parties could deliberately change how they select candidates to get a greater values diversity (Settlers, Prospector or Pioneers), and subsequently promote them to leadership, making them a more similar mix to the actual electorate. [Note that although ‘progressives’ are disproportionately Pioneers, not all are, for instance many libertarians are probably Pioneers]. Rather than ideological, political theory or national or international ‘issue’ knowledge, greater emphasis could be put on practical local experience of negotiating agreements across party differences and with communities.

Support local newspapers. More in the culture of Europe than the US perhaps but the evidence for community benefit from local news is significant. One study showed that:

When a local newspaper in California dropped national politics from its opinion page, the resulting space filled with local writers and issues …. after this quasi-experiment, politically engaged people did not feel as far apart from members of the opposing party, compared to those in a similar community whose newspaper did not change.

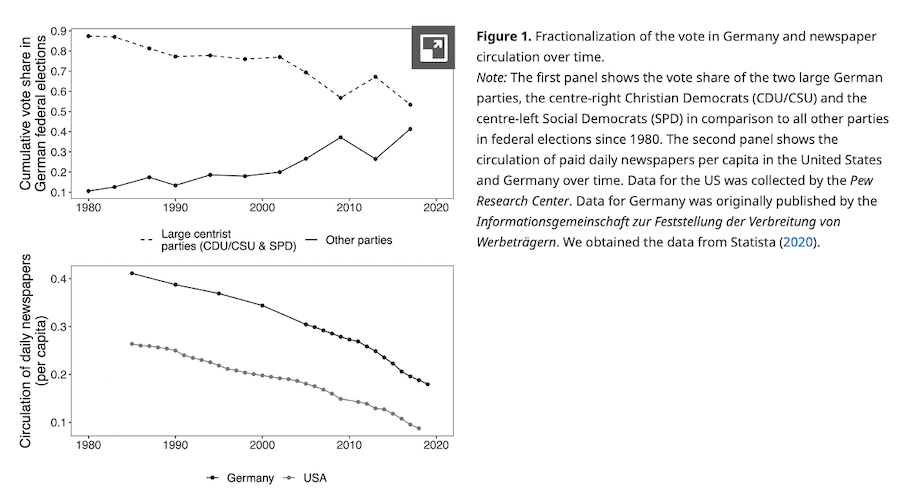

Research in Germany demonstrated that between 1980 and 2009, from electoral returns, and an annual media consumption survey of more than 670,000 respondents, ‘local newspaper exits [ie closures] increased electoral polarization’.

From Fabio Ellger et al, 2024 Local Newspaper Decline and Political Polarization – Evidence from a Multi-Party Setting

Political communication strategists could avoid moralisation of propositions in terms of ‘right or wrong’ and eg ‘power’ or ‘universalism’ and instead focus on pragmatic framing and reasoning (eg true/false, what does or does not ‘work’). A 2024 study by Jae-Hee Jung from the University of Houston and Scott Clifford of Texas A & University proposed this after finding that in 1-1 communication, ‘moral values are uniquely divisive’.

They showed that discovering that someone disagrees with such a belief that you hold, has a stronger polarizing effect than finding they hold moralised beliefs you do not. They concluded that ‘appeals to more self-oriented values are likely to persuade without leading to attitude moralization’, meaning ‘pragmatic’ what-works propositions (Prospector logic in CDSM values terms) rather than ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ framings determined for Settlers by morals, and by ethics for Pioneers.

Allow for values diversity at a local level, rather than imposing narrow values-loaded communications or policies from the national level top-down. A large body of evidence shows that media consumption has become ‘nationalised’ and the news agenda has narrowed.

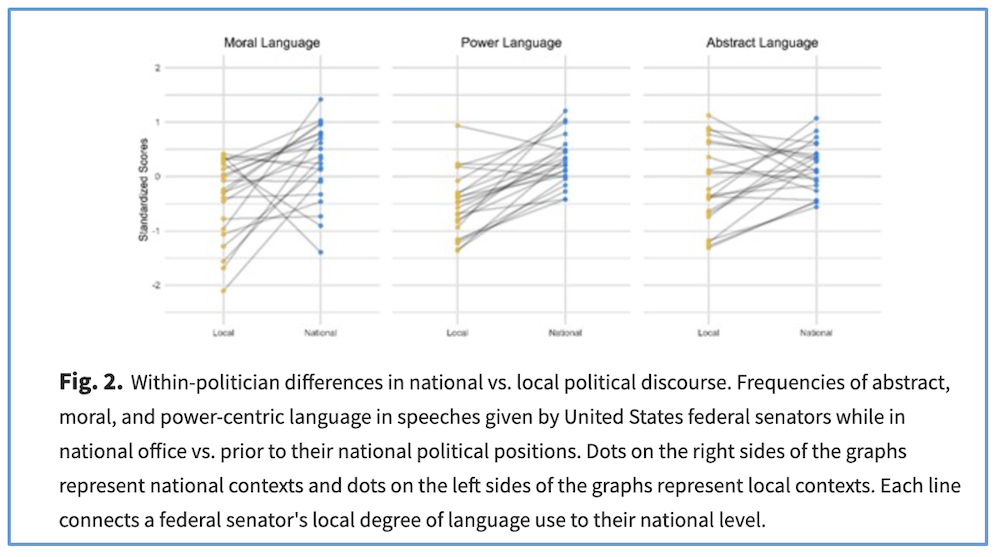

A 2024 study in the journal PNAS Nexus showed (below) that polarization is stoked by ‘nationalising’ of local news because national politics is framed in more polarizing and moralised terms (eg about power), even by the same politicians (here as in speeches before and after candidates they got elected to the US Senate).

The researchers led by Dancia Dillion of the University of North Carolina Department of Psychology, found that:

‘Unlike local politics, which can rely on shared concrete knowledge about the region, national politics must coordinate large groups of people with little in common. To provide this coordination, we find that national-level political discussions rely upon different themes than local-level discussions, using more abstract, moralized, and power-centric language. The higher prevalence of abstract, moralized, and power-centric language in national vs. local politics was found in political speeches, politician Tweets, and Reddit discussions. These national-level linguistic features lead to broader engagement with political messages, but they also foster more anger and negativity’.

In practical terms for example this could also mean that rather trying to address a national audience with single arguments (‘messaging’) for a policy, showing that it has widespread support at a local level, could evidence that it ‘works’ while allowing for a diversity of values-based tuning to suit the values make up of different areas.

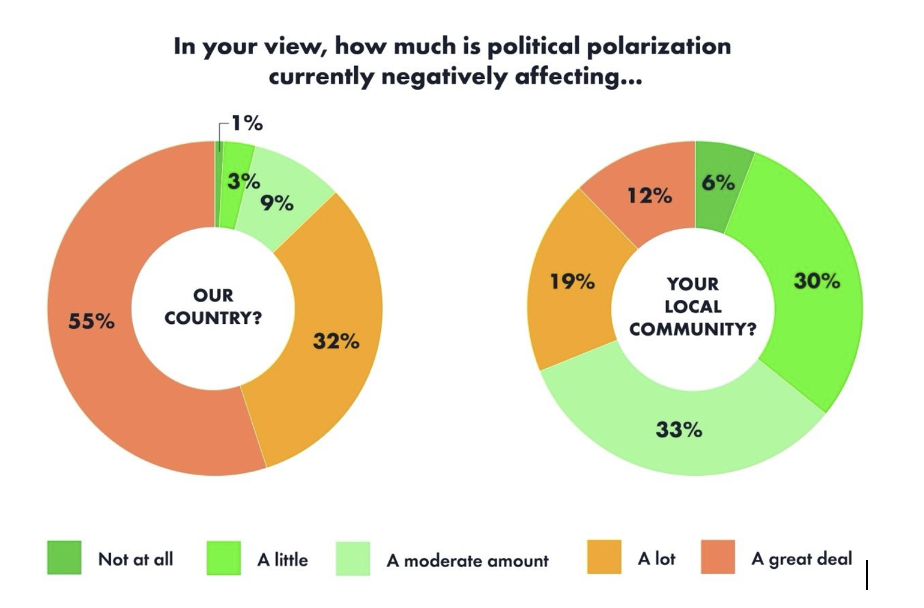

A local-up rather than top-down approach could build on the existing greater tolerance of differences at a local level. Another 2024 US study, by Civic Pulse/Carnegie found from surveying over 1,400 elected politicians and officials in local government that ‘an overwhelming majority of local government leaders (87 percent) believes polarization is hurting the country but far fewer (31 percent) see negative effects in their own communities’. They concluded that (while not without its problems detailed in the study):

‘Local governments are largely insulated from the harshest effects of polarization in America, and communities below 50,000 residents are especially resilient to partisan dysfunction due to greater participation in local activities and a shared focus on tangible needs and services’.

Civic Pulse/ Carnegie study – views of elected and professional officials/leaders in US local government 2024

The study discovered that three of the ways respondents cited to overcome polarization included:

- Participating in local activities buffers ideological differences –Local officials pointed out that because they live in the same community and participate together with constituents in local events, they are more able to recognize their shared interests and values.

- Focusing on concrete needs helps depolarize local politics – Respondents highlighted the importance of focusing on tangible community needs and services, such as infrastructure maintenance and disaster response, to overcome partisan differences.

- Reducing emphasis on political parties leads to better day-to-day governance – Respondents said that keeping candidates’ parties off local ballots and other measures to deemphasize party affiliations help to foster an environment where community-focused decision-making transcends partisan boundaries.

Basic Values Examples Related to Politics

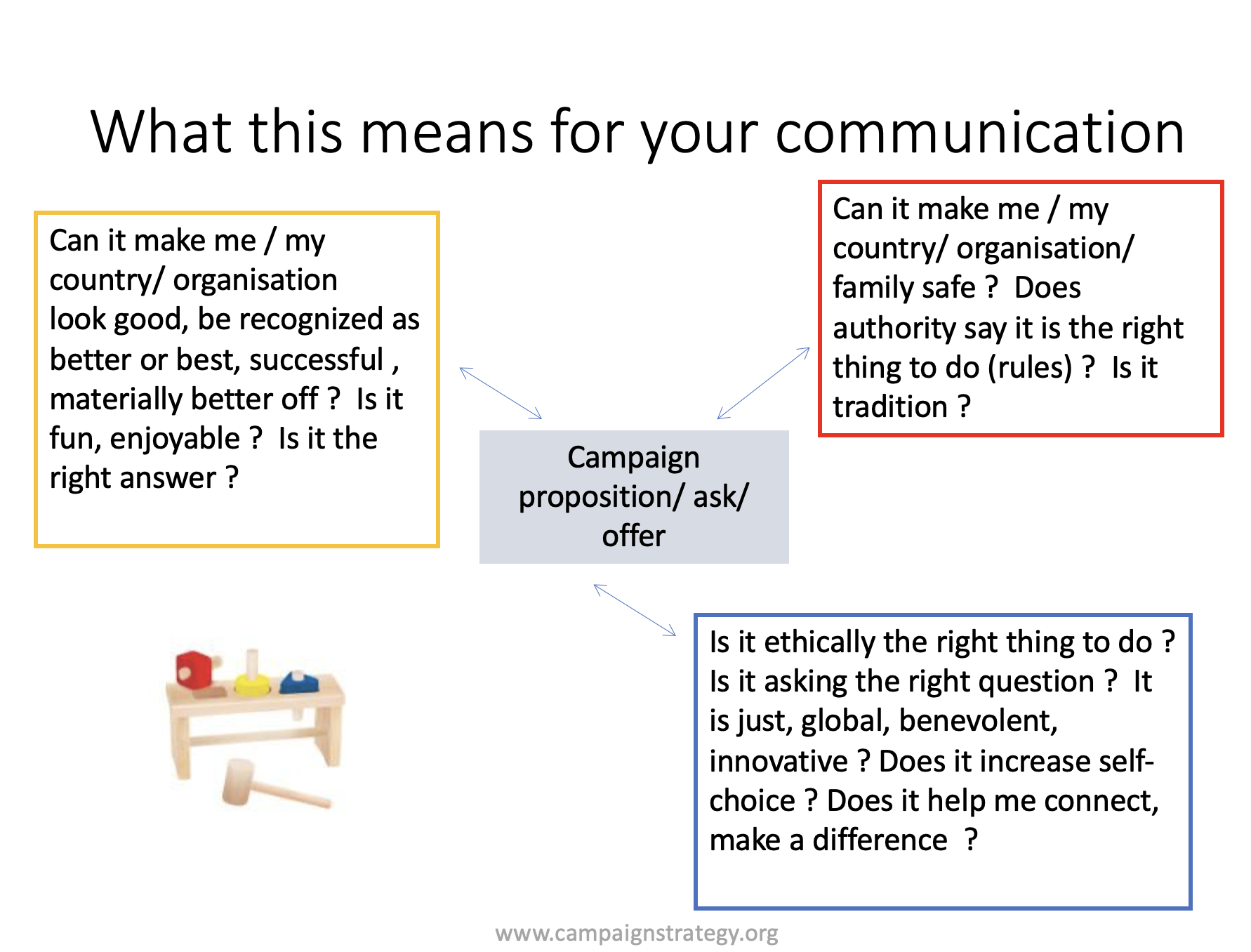

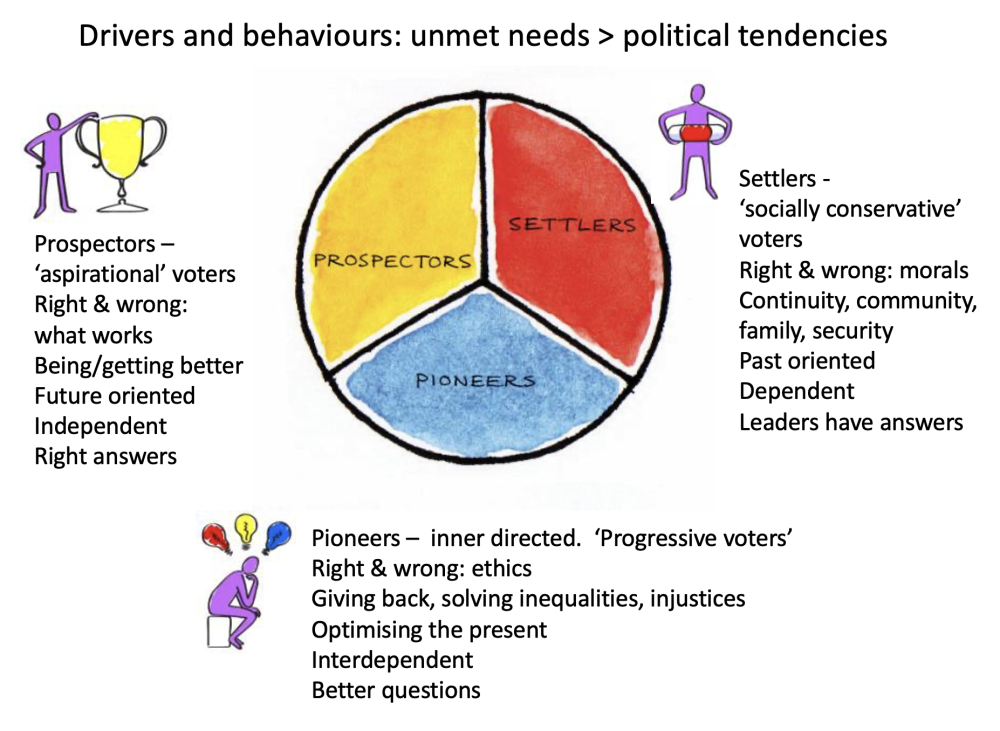

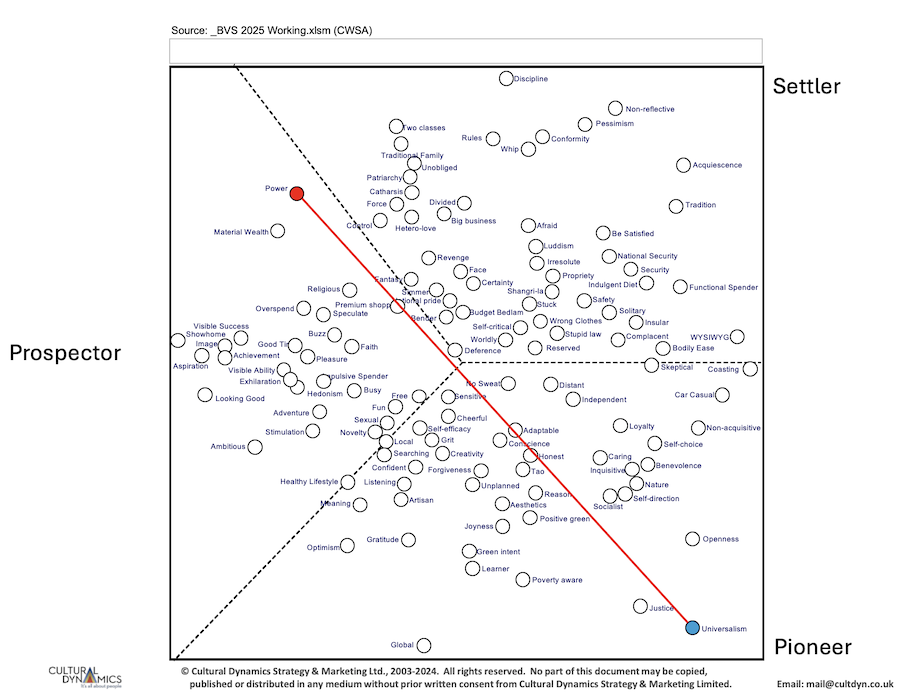

The values I am talking about are not philosophical or political values but motivational human values as mapped in academia by Shalom Schwartz, charted in different ways in the World Values Survey, and defined as recognizable real-life values groups by Sinus Milieus based in Germany and Cultural Dynamics in the UK, all ultimately springing from the work of Abraham Maslow. Importantly, they are independent of ‘political values’. CDSM’s mapping identifies three large Maslow Groups and 12 more distinct Values Modes separated by their deep-seated attitudes and beliefs, which exert an effect on everything in life, not just politics.

Non-political schematic of values map: Settlers have an unmet need for safety, security and identity; Prospectors for esteem of others then self-esteem; Pioneers for ethical-clarity, then self-expression and practical ethics, integration and self-actualization. (Maslow Groups).

Non-political: some of the sorts of questions different Maslow groups ask of a proposition.

Outline of generalised politically relevant tendencies by Maslow Group

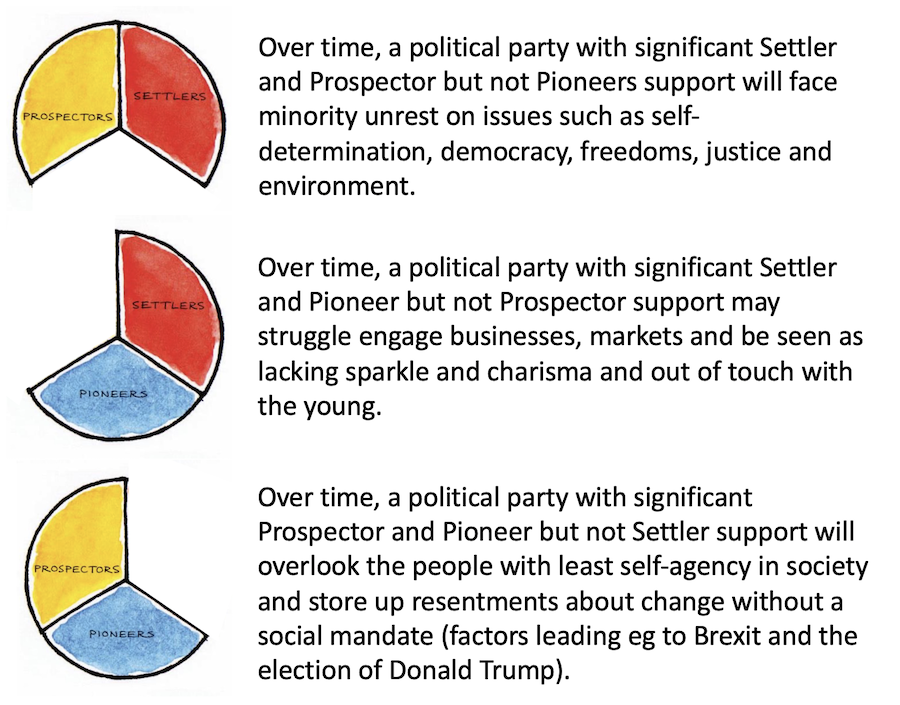

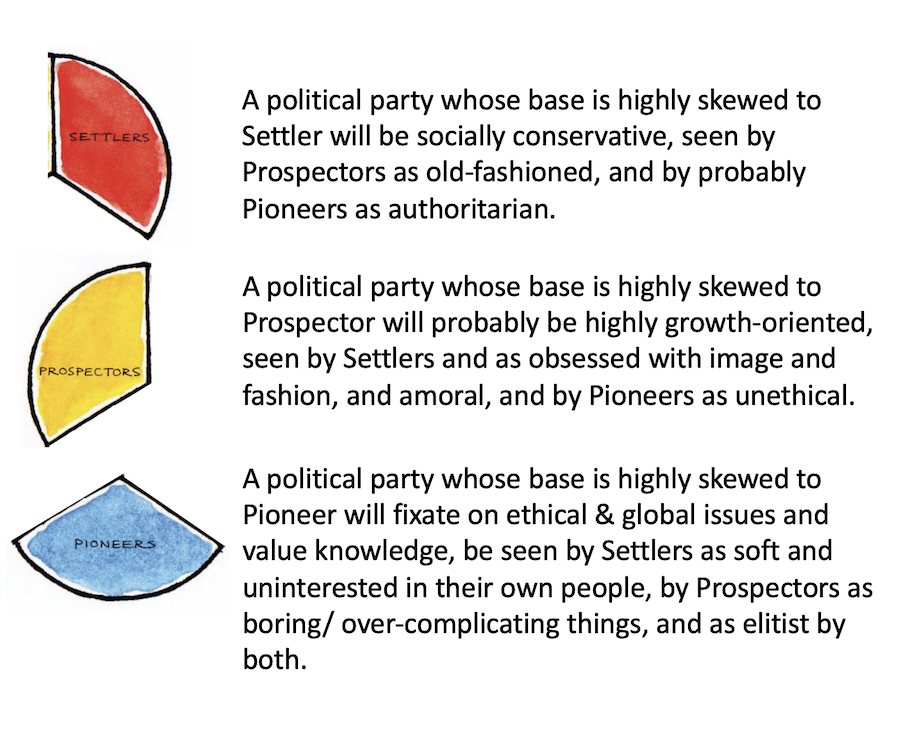

Some parties have a narrow values base. These are some possible implications.

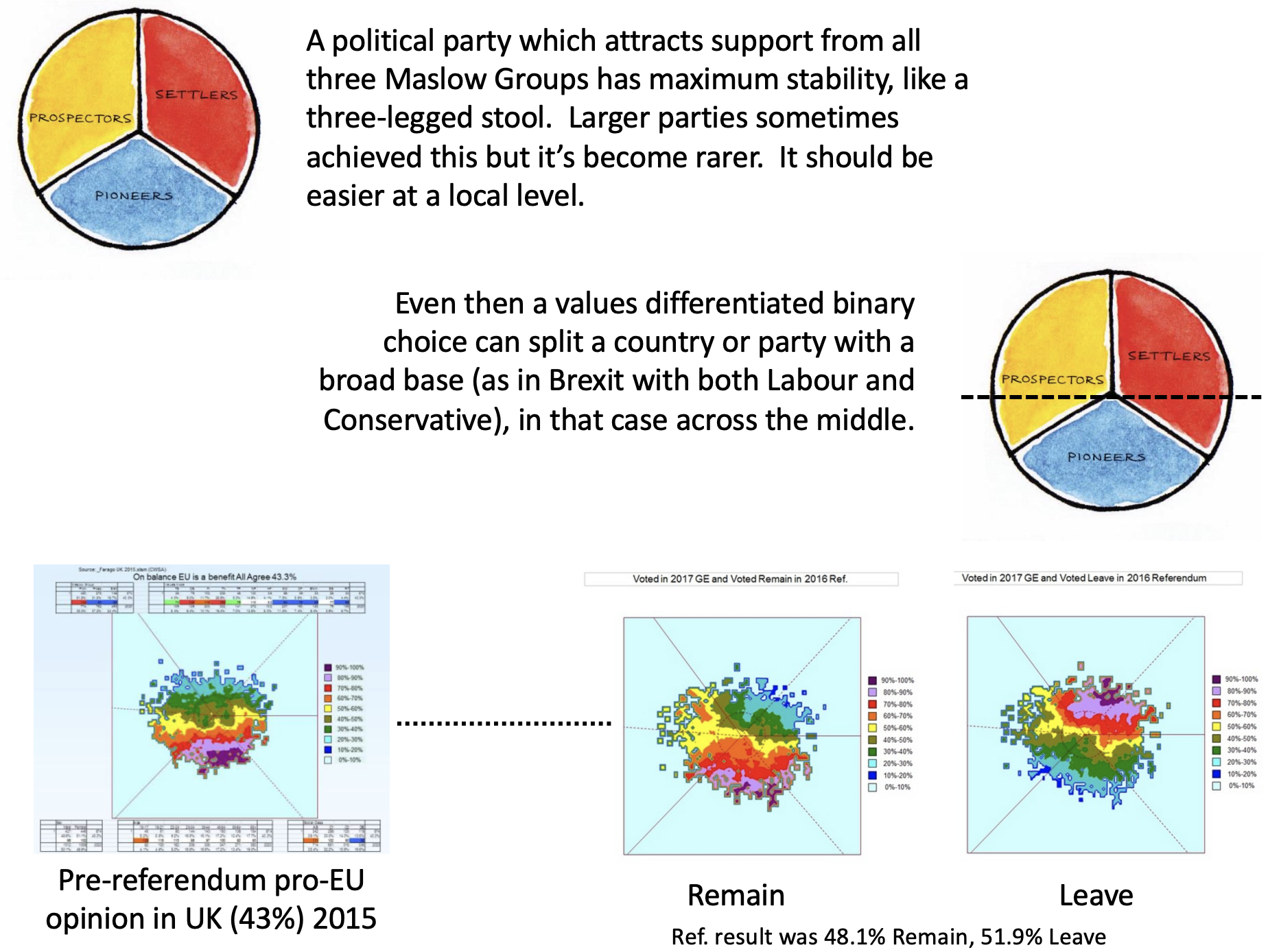

Some parties (and governments) succeed in appealing to two groups but not the third.

This last effect is probably behind some of the distrust in the mainstream political system across much of Europe, despite the previous stability of mainstream parties.

So What?

What then of the choices facing the Dem’s in the US? The media hot-take was that it posed the Democrats a strategic dilemma – should the party follow Route Spanberger through the political centre, or Route Mamdani to the ‘left’.

Of course Mamdani’s New York platform replicated nationwide could easily be polarizing, whether gamed by Republicans or by default. And various pundits then pointed out that the Democrats could have a mixed strategy with Spanbergerish candidates in most places and Mandamites in places dominated by progressive-cosmopolitans (read, in values terms, Pioneers), like California. Besides, that’s what the Primaries system allows for – various forms of local choice. Then of course, they also do have to select one person as a candidate to be President.

These are important electoral questions but not in the longer run, the most important question for governance and society. Finding ways to de-polarize and govern successfully with values-diversity, seems to me to be a greater challenge for politicians everywhere, not just in the United States.

And finally

For enthusiasts, here’s the actual British Values Survey map from the CDSM model (2025 version). The current UK values split is 27.9% Settler, 38.6% Prospector, 33.5% Pioneer and probably similar in many EU countries. There is no recent US Survey I know of.

from Pat Dade of Cultural Dynamics Strategy & Marketing showing Power v Universalism, the commonest polarization axis in western politics

[I hope to have a more extensive paper about politics, values and polarization published in the New Year. For more on motivational values see my book What Makes People Tick: The Three Hidden Worlds of Settlers, Prospectors and Pioneers. ]