Chris Rose

(You can also download this blog as a pdf)

I have to confess that for the past several years, something has been worrying me about stories. Not stories in general: like everyone I guess, I love stories. It’s only human to do so.

It’s stories-in-campaigning that worry me but not even just that as such. I’m a ‘believer’ in their power and have my own pet lists of useful things campaigners ought to know about stories[1]. I’ve long tried to emphasise to would-be campaigners that the two most important things in communicating for campaigns are to use stories, preferably involving real people, and to communicate through pictures.

It’s more about the contemporary fashion for stories, or rather for adopting techniques of ‘story-telling’, which to me at least, sometimes seems to have become more than a tool and almost grown into a belief-system. When I hear that ‘great story-telling will lead to ‘great campaigns’, something shouts at me that this isn’t right. Not on its own. So great is the vogue for having a campaign composed of great story-telling that I have seen almost any sort of campaign communications which campaigners are proud of, described as ‘great storytelling’; from linear videos, to photo-calls, to print adverts to physical actions, to infographics.

Asking for Help

Some readers of Campaign Strategy Newsletter may remember that a couple of editions ago I asked for help. Did anyone have evidence of where story-telling had actually produced results in campaigning ? I didn’t really doubt that they had but I wanted to know how they had, and how we knew they had.

Thank you to those who took the time and trouble to write to me[i].

This wasn’t the first time I asked, and I’ve been sent lots of links to some of the mountains of evidence of how stories work, or how story-telling works although rather little evidence of how it made a difference in campaigns.

For instance people sent me examples of using personal stories to give a voice to immigrants in Belgium (at festivals); how the World Bank tried pitching itself as a ‘knowledge bank’, which was unsuccessful until it started using stories to show this; how Medi Tech did something similar with individual stories of benefit; how NGOs such as Oxfam used human stories to help lobby on climate, and how WWF deployed stories about the impact of climate change on individual business to make a greater impact in lobbying on the EU Emissions Trading Scheme; and how by collecting personal testimonies about how ‘ordinary’ people got involved in locally opposing fracking, this helped others realise they could do the same.

You probably know of many similar examples. So I am sure it does make a difference if you switch from ‘information’ to ‘stories’ and from impersonal to personalised stories. Yet even as I asked for help I knew that I wasn’t really asking right question.

I tried committing my thoughts to ‘paper’ and circulated them to some friends, with very mixed results ranging from ‘hugely important – if you publish, can I repost it ?’, and ‘this troubles me too’, through ‘what you are missing is …’ to ‘this is so important that we need to sit down and talk about it’ (which never happened).

Still it nagged at me, or as they said in one of my favourite stories, ‘it called to me’.

Things That Troubled Me

It troubled me that the current vogue for ‘story-telling’, might accidentally become an end in itself, in a similar way to that in which ‘publicity’ for campaigns and media coverage once often served as a proxy for getting results in terms of change. But it wasn’t only that.

It also seemed to me that skills or formats of story construction (such as The Hero’s Journey) were being uncritically imported into campaigning when these worked just fine in other contexts, for example film or theatre, books or indeed, face to face ‘traditional’ tale spinning but didn’t necessarily do what was needed in campaigns, and certainly didn’t constitute campaigns.

It concerned me that campaign groups adopting story-telling so enthusiastically seemed to have been influenced by the fashion for personal-story story-telling in ‘movement making’ in American politics (eg Marshall Ganz and the ‘story-of-me’, the ‘story-of-us’ etc), and in the corporate world, which has invested heavily in story-telling as a way to gain brand penetration in ‘digital’, including in social media networks, or for making a pitch to a face to face audience (such as the six stories ‘you need to know’ by Annette Simmonds[2]).

These story-doctrines come with their own high caste of practitioners, who may have found a new market in campaign groups wanting to be ‘professional’. But also it worried me that this worried me ! After all, I am an advocate of eclecticism, ‘being a magpie’ and borrowing or stealing any good ideas that work (see my book How to Win Campaigns, as a compendium of stolen ideas). Plus I’m a consultant too. Was I suffering from a case of sour grapes or contract envy ?

Then I wrestled with the fact that whenever I tried to pin down the elusive ‘problem’, digital or new media kept comparing itself in my mind with the age of mass media, which I grew up with as a campaigner, and is undoubtedly passing, if maybe only transmuting into new forms. This transition seemed somehow central to whatever the problematic ‘thing’ was, and yet I was painfully aware that I didn’t want to pour cold water on ‘digital’ just because I am a campaigner with roots in another age.

Sure enough one friend, an arch-exponent of digital story-telling, commented on a draft that it “sounds a bit like pining for the old days of corporate-controlled but mass-audience media, my friend”. Ouch. That’s what I was afraid of.

So this is why my Newsletter output got rather thin. Every time I sat down to try and write about ‘stories’, the problem eluded me like a fish that got away in a dream.

I now think it boils down to:

- Campaigners should primarily be story-makers not story-tellers

- Real-world experience is fragmentary – most often the audience makes the story from fragments: most do not see, hear, read or experience any complete story created by the campaigners, so being trained in story telling techniques designed for audiences who consume the whole story, is not a training for real life campaigning

- Audiences are at a premium in the digital age: those made by mass media are draining away, so there is a strategic need to create audiences that stories can be told to, whether through ‘digital’ or in real life, and whether as fragments or in complete form

- Most campaigns have to use stories to get where they want to go: stories to motivate, to explain and to organise but campaigns also have to ‘make stories come true’, and story-telling itself is rarely sufficient to achieve that.

Put these together, and you have the source for my disquiet, my trouble with ‘stories’ as a centre-piece of campaign making.

Good Skills To Have, An Important Process to Understand

Stories are without doubt the oldest form of advanced human communication. “Come this way” to find food, shelter or avoid enemies, must have been a very early form of story. “Go this way” and “this is how to do it” might have been next. Add in explanations for things that puzzled people, such as why the sun went up and down, the seasons changed or animals came and went, and how to anticipate such things, and you have many of the basics of human society. Include why we exist and what happens when we die, and how to treat each other, and we have much of the rest, including creation myths, religions, moral tales and fairy stories.

Not surprising then that our brains are ‘hardwired’ to deal in stories, and that stories are the ‘stickiest’ form of communication: easier to recall and process than facts and figures, logic, argument or analysis. A welter of neuroscience and other psychological research confirms this in scientific terms. Eg [3],[4],[5],[6],[7],[8],[9],[10]

Because you can ‘see it happening’ on brain scans, and boil some if it down to the role of identifiable molecules like that of oxytocin in generating empathy, it’s all very exciting to communicators. But essentially science is explaining, unpicking and most often confirming what story tellers have known for millennia, for example the power of stories to ‘transport’ us, to ‘take us there’, to inspire and to get us to identify with a character.

The many powers of stories come about because we are more like animals than machines but that also applies to why ‘pictures work’, and experiences work, and how framing, heuristics and motivational values[11] work.

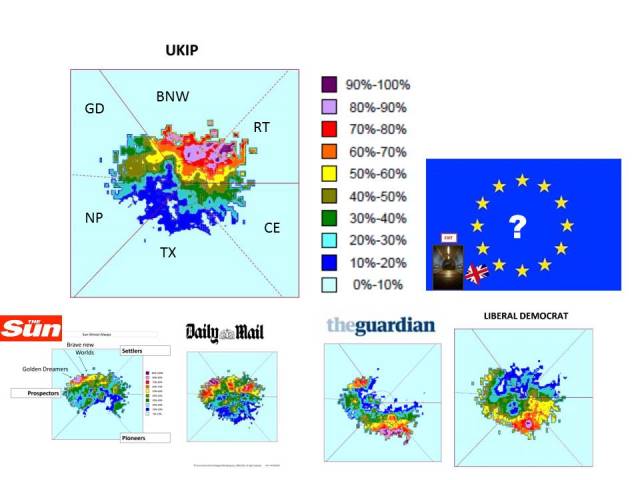

These things interact. Many of the story formats most popular with movie makers and analysts of stories for instance, such as those in which a hero overcomes obstacles to do what is morally ‘the right thing’, are firmly Settler stories. For Settlers right or wrong is decided by morals, social rules given to us by others, by authority (eg god, parents, ancestors). They speak to our most basic needs, and they predominate in the stories we tell our children.

In Prospector World right and wrong is no longer subject to universal rules: what’s right is what works, for me, for us, and us can be a changeable category. There are probably fewer pure Prospector stories which we turn to for entertainment, certainly ‘family entertainment’.

Few fairy stories or popular movies end with the protagonist becoming far richer or more successful than his or her contemporaries and simply or ‘selfishly’ enjoying themselves. We tend to prefer other versions in which they return to Settler values, or maybe transition to the wisdom of Pioneers and see the bigger picture. In James Cameron’s Avatar, a movie so transporting that it was said some people sought psychological help for the distress caused by not being able to actually move to planet Pandora, the space warrior (Settler hero format) earns his place in local society (more Settlers), and leaves the Company (Prospector exploiters), succeeding where the Concerned Ethical type Pioneer scientists fail. It’s a fantasy which paints in strong values colours and only shows the good or bad side of Settler or Prospector values to suit the story.

Martin Scorsese’s Wolf of Wall Street is based on a true story and the values mix is more complicated. At times we empathize with Jordan Belfort and although he gets his comeuppance after mindboggling hedonistic excess and selfishness, time and again it shows the inspirational nature of aspiration (Prospector values). Even at the end, the human appetite for bettering themselves in material terms, is not extinguished.

In real life, aspirational, mostly Prospector stories abound: for example in business and other places where success and power are good and the audience does not want to question that, because it’s a success or power seeking audience. Sport too has many such stories.

The Baker’s Adventure

At least one Hollywood screen-writer is said to use Cultural Dynamic’s motivational values to breathe life into characters. Have a look at this basic guide to communicating with the three Maslow Groups. One important way they differ is in things like resolution and change. Imagine for instance that your story involves a baker and bakery. Calamities befall them and adventures ensue and challenges are overcome. As the dust settles, how should it end ? Obvious options might be:

After all that, the bakery is still there, the baker has come home and is baking the same bread, which is as popular with local customers as ever. (Settler – getting back to the centre, not losing the past, maintaining continuity).

And the baker ? He went on to build a business that now supplies bread and rolls right across the country. You probably ate some for breakfast. (Prospector – it all got bigger and better).

And the bakery ? It’s still there baking the same bread, and as popular with local customers as ever. But as to the baker, he was never seen again, although there are rumours that … [fill in something which hints at a wider version of the ethical or universalist out-take from the resolution] (Pioneer – pulling it together for everyone’s benefit but also open ended).

That’s a rubbish example and lacks any story content but maybe it helps make the point. Here you can also find the more detailed differences between the four Values Modes of Settlers, Prospectors and Pioneers.

Pioneers will accept, indeed quite like, an unresolved story. Here’s an example from an RSPB mailer which broke fundraising records. It was designed to appeal to Pioneers and written to cover as many Pioneer ‘hot buttons’ as possible.

It’s a story but with no ending. It is told by a fen (a sort of marsh). That wouldn’t work well for Settlers (fens can’t talk ! not in definitive Settler world). Nor for many Prospectors: it’s ‘weird’. But for Pioneers, why not ? Let’s imagine, that’s interesting.

It’s also lyrical, poetic and has no ‘facts’ (Prospectors: “where’s the proof ?”, “where’s the target ?”). It’s just values and emotion, open questions, mystery, beauty, and indeterminate: many Pioneers love this sort of stuff.

Deception

Stories can also powerfully deceive us because they can make things ‘true’. When Prophecy Fails[12] is a famous example of the capacity of human beings – in this case a cult group who believed in an impending apocalypse – to rationalise evidence in order to reinforce existing beliefs rather than change them. The cult began with a story in a newspaper, about a housewife who had accessed supernatural powers to reveal an untold truth transmitted from Planet Clarion. When it failed to arrive after they stayed up all night, the followers retained their belief but persuaded themselves that their life of example had saved earth, and now they had to urgently spread the message wider. (The cult leader’s husband was a non-believer who slept through it all).

As Daniel Kahneman[13] and others have shown, and as countless propagandists have exploited, ‘cognitive ease’ exerts such a pull on our critical faculties, that we have a bias to believe whatever is easiest to understand. Of all the things that makes a story a ‘good story’, the truth hardly ever registers. Or as the old journalistic cliche has it: “This story is too good to check”. We mostly like to believe what ‘feels right’.

The Enlightenment challenged the acceptance of stories which had previously been accepted as absolutely true. It increased empiricism, paving the way to the scientific method, evidence based policy and analysis. Campaigners now have to be able to deal in both worlds: the evidence-based realm of Kahneman’s analytical ‘System 2’ , most elevated in science, and the animal communications of intuitive processes (his System 1), easier and far more persuasive.

Neuroscience is now revealing how and why stories work and no doubt bringing important new insights for practitioners, such as advertisers. It’s using System 2 to investigate System 1. But thousands of years of trial and error have also left us with a huge legacy of story telling techniques and formats. These are a treasure trove of ideas for story telling, including in campaigns.

‘Traditional stories’ and novels are an important source but as media students discover to their cost, dissecting the structure of stories and making up ‘rules’ about what’s right, has reached its zenith in theatre and film. There is a vast literature, such as Robert McKee’s Story[14] aimed at screenwriters.

And there is a huge store of rules of thumb such as ‘Chekov’s Gun’[15], a trope or plot device which says don’t put anything into a story which won’t serve a purpose. It’s a good general principle including in communications outside stories; less is more, don’t include anything in your motivational campaign communication which is not essential to getting the audience to take the next necessary step. Likewise a MacGuffin, or thing which the protagonist and maybe others seek, and around which the story turns. For example the ring in Lord of the Rings.

Then there are attempts at laying down general principles, such as Joseph Campbell’s ‘monomyth’[16] of the Hero’s Journey. It’s current popularity in story-telling training and amongst NGOs may owe something to the nice diagram of it apparently redrawn from a 1985 Walt Disney Studios memo. It was popularised by Christopher Vogler in The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure For Writers[17] and before him Bill Moyers The Power of Myth[18] based on tv interviews with Campbell.

source: Wikipedia

Wikipedia reproduces[19] Voglers’ summary of the Hero’s Journey thus: 1. The Ordinary World, 2. The Call to Adventure, 3. Refusal of the Call, 4. Meeting with the Mentor, 5. Crossing the Threshold to the “special world”, 6. Tests, Allies and Enemies, 7. Approach to the Innermost Cave, 8. The Ordeal, 9. Reward, 10. The Road Back, 11. The Resurrection, 12. Return with the Elixir. It summarises it as ‘the common template of a broad category of tales that involve a hero who goes on an adventure, and in a decisive crisis wins a victory, and then comes home changed or transformed’.

Not everyone agrees with its importance. Blogger on narratives James Hull writes[20]:

‘There is a sickness running through the world, a sickness that attempts to twist every instance of narrative fiction through the siphon of errors that is the “Hero’s Journey” story structure paradigm … The Internet teems with those who think every story is the same and that this similarity can be attributed to man’s need for mythic transformation.

There can be nothing more destructive to the world of storytelling than this compulsion for spiritual metamorphosis. Stories are about solving problems. Sometimes, solving those problems require the centrepiece of a story, the Main Character, to undergo a major transformation in how they see the world. Sometimes they don’t. There is nothing inherently better about a story where the Main Character transforms’.

It’s easy to get lost in the academic world of story analysis. For example in arguments about the differences between story, plot and narrative[21],[22],[23],[24],[25],[26],[27],[28] or whether as (I’m told[29]) Aristotle maintained, a ‘good story’ has an inciting incident, a climax, crisis or turning point, and a resolution.

A lot of the arguments apply mainly to particular forms, such a film. Given the literally linear nature of film or video, departures from linear storylines are of particular interest and many film students who took up the subject because they enjoyed films, are subjected to watching movies like Memento (a non linear film about memory loss) because it does so with such enthusiasm:

‘The film doesn’t start at the beginning and lead us through to the end though. In fact, the narrative is far more complicated than that. To be as simple as possible, the film is actually shown backwards in fifteen minute increments. There are also some scenes in colour and others in black and white. Those in colour are a reverse order scene and the black and white scenes are in chronological order. It’s complex but an interesting example because the film makers could have started at the beginning and kept it linear but they wanted to tell the story in a different way’[30].

After too much time reading about stories, my favourite exchange was this one online:

Puzzled student:

“What is the difference between a story, text and narrative in terms of literature?

Best Answer – Nihl_of_Brae answered 7 years ago:

“Your best bet is to ask your instructor, because that is the person who will be grading your test. My understanding may be different” (Nihl did in fact go on to give an answer[31]).

There’s lots more. For instance philosopher Tvzetan Todorov[32] saw narrative[ii] as equilibrium, then disequilibrium, and a new equilibrium while anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss [33] decided that the creation of conflict propels a narrative, until it gets resolved. Others say more simply that plot or story is what happens, and narrative is how the story gets told, for example from whose point of view.

But rather like the search for a Holy Grail ‘Theory of Change’, which once discovered will be a recipe to make your campaign successful, learning more and more about story-telling formats and methodologies is unlikely to solve many of your problems in campaigning unless you take much more into account, which is not about the structure of your desired story.

Stories You Can Tell and Stories People Make

In real life, very few campaigns can be won by only communicating with people to whom you can tell a complete story. For this reason, a great deal of the store of knowledge about the craft and theory of ‘good story’ structure is not very relevant to making campaigns in real life.

Nearly all of traditional storytelling practice, film-structure theory, academic analysis of what works in literature, even digital story-telling in immersive games, takes it as read that there is an audience who will ‘sit through’ the story. They can get the complete story.

This is true in a movie theatre or a live play. Not many people get up and walk out. Most see the beginning, the middle and the end, whatever the plot or narrative structure.

Even fewer get up, walk out and come back near the end, and then happily make up ‘their own mind;’ about what the film was about. But that’s much more what happens with most audiences you need to reach, and that’s on a good day for audience attention.

Traditional story-tellers can see if there is turnover in an audience but in the main, once you are ‘inside the tent’, the ‘teller’ has your attention from start to finish. The beginning to them is the beginning to you. Not necessarily so with campaigns. People may only see the start, or hear about the inciting incident in Act 2. They may assume that it ended after that, and never be aware of what ‘finally’ happens. And that may not matter. Indeed for many of the most significant campaigns, by the time you finally ‘win’, even the ‘issue’ is quite often forgotten, or has ‘moved on’ and transformed out of recognition.

We may pick up a book and read it through at a sitting ‘cover to cover’ or do so in small portions before bed or while commuting but for the most part the author will be safe in assuming that anyone consuming his or her work, starts on page one and ends, at the end. If we put a book down and come back to it later, we usually mark the page to ‘pick up the thread’ of the story. If we read a book we want to follow-the-story. That’s not necessarily the case with a campaign.

You may well have had the experience of doing some research into what ‘the public’ or even a supposedly well-informed audience like your colleagues or your Supporters, actually know about your campaign. They will rarely even be aware of most of your attempts to communicate with them. They may be enthusiastic and supportive but completely wrong about some of the basics. Carefully drafted reports, blogs and mailings may have been wasted, although not if they have anyway done something useful.

All too often that’s not the case. I remember lying in Whitehall outside Downing Street, nominally dressed as a corpse for a Greenpeace anti-nuclear campaign. There being 600 such ‘corpses’, the police had to wait for reinforcements to arrive before dragging us away. I listened as two nearby policemen discussed our campaign. “They should have gone to a shopping centre instead” said one, “a much better place to hand out leaflets”. “Yes” said the other one, “That’s how you get public awareness about things like tropical forests. My missus always gives a donation”.

In the sense of a ‘narrative’ being a consistent ‘story’ into which events (and bits of other stories) fit and which makes them make sense, this perhaps shows there was a ‘Greenpeace narrative’ of attempting to engage public opinion through ‘protest’. It was just that the two policemen had simply recalled the most recent and most salient campaign (the availability heuristic) they had come across, in order to make a ‘story’ about what we were doing at that moment, which to us was ‘wrong’.

No doubt what Greenpeace ‘sent out’ in the communications it controlled was a story that made sense and was about the nuclear issue in question (THORP) but that’s not the point. It’s what people conclude that matters.

Admittedly in this case it was done to try and get the news media to tell a story, and that did work in the sense that next day there were some newspaper pictures with accurate captions but even that’s not the end of the story. If people already think they know what you are trying to say, that’s what they will hear or see.

Those corpses lacked labels and campaigns often include their own captions in the form of banners or placards to try and make sure that ‘the message gets across’ but even that may not mean it is truly ‘installed’ in someone else’s head. Around the same time, early one morning Greenpeace climbed part of the British Houses of Parliament and hung a huge banner which did in fact say something about saving rainforests. The TV showed the banner, and the newsreader announced we were conducting a protest about “Trident” (Britain’s nuclear armed submarines). So I picked up the phone and rang the breakfast TV news desk: “I’m calling from Greenpeace; your piece just said we are doing an action about Trident” I said. “So ?” responded a bored-sounding Australian voice. “Well have you looked at the banner ?” I asked. “Ah yeh, see you mean” he said. “So why did you say it was about Trident ?” I enquired. “’cause that’s what the police told us it was about” said the journalist.

So campaigns tend not to get consumed or experienced in the ways that are assumed in most story formats. And most campaigns are too diverse over time, or simply too long and often too boring, to be effectively told as stories. For this reason stories do not tend to create campaign strategies, and your real strategy cannot usually be turned into a motivational story.

Strategies That Should Not Be Stories

Indeed your real strategy should usually not be a public story. This is obvious at a tactical level: for example if you need to surprise or deceive an opponent. As Sun Tzu said[34]: ‘Generally, in a conflict, The Straightforward will lead to engagement, and the Surprising will lead to triumph.’

Strategy-making requires things like situation analysis, power analysis and intelligence gathering for insight. This has nothing to do with telling stories, as often becomes apparent when journalists or film-makers get the bug and decide they are going to try a bit of campaigning to change real-world outcomes. Their skills and techniques may be great but they are more likely to lead to engagement, either in the sense of creating a conflict with an opponent or engaging the converted (or both), than in triumph.

Strategy requires making choices about which changes to try and achieve. For instance for political reasons it may be more useful to induce certain companies to shift position on a subject, than to target others, or to try and change institutions or individual behaviours, even though they may make up a much bigger part of ‘the problem’ but if as targets they lack political leverage and that’s what the next breakthrough to strategic change requires, they are not good targets. So to change the decisions of the politicians we might need to change the actions and positions of companies. And to change the positions of companies we might need to involve consumers. Plus what interests the companies is probably not what interests the consumers and vice versa, and so they need different stories, and there is normally no benefit in them hearing the story you tell to others.

Real campaigns offer many more possible choices than this and the stories that may be needed have to be defined for each audience engagement, as you move from one objective to the next, along a critical path that leads to a final change objective.

As a campaign unfolds and moves from one objective to the next, the supportive audiences and targets are likely to change. This means that many people will only experience one part of the ‘campaign’s story’.

This does not mean there is no value in telling stories, only that story-telling is not strategy-making. Yet I have come across campaigners, especially ‘digital campaigners’, struggling to solve campaign problems that are essentially strategy issues but trying to create a story to do so. It’s a bit like asking the press to run your campaign for you.

Three Useful Stories

Three stories that do not drive a campaign but are anyway often needed are the Public Story, the Professional Story and the Political Story. These are all stories about what the campaign is, not stories that make it work.

The test of the Public Story is that it can be told without jargon and in terms that ‘the public’ can understand. For example your neighbour, your mother or sister: test it as crudely or in as sophisticated a way as you like. This should be your default explanation of what you are doing, why, and what it will achieve in terms of problem, solution and benefit. It has to work in terms of intuitive reasoning, Kahneman’s System 1.

The Professional Story probably needs jargon because it must be ‘precise’, or at least speak in terms that key ‘expert’ audiences recognize as showing that you know ‘what you are doing’ in their terms. Use of jargon is a shorthand indicator (System 1) that you have ‘thought it through’ in their terms, and can make an ‘analytical’ case (System 2). This should never be allowed into the general public domain because it will be incomprehensible. A campaign is not generally an opportunity to educate the public into becoming experts.

The Political Story is rarest. It should be reserved for politicians who need to be engaged, whether to join in or give way, and needs to explain benefits in their terms. These are nothing to do with ‘the issue’ but things like generating popularity amongst voters or key interest groups, gaining promotion, retaining their seat, undermining the opposition (and better still, rivals), and possibly pleasing their families. It needs to be elevator pitch short, as politicians at least like to think their time is so valuable that nothing can be longer. Do not annoy politicians or advisers by explaining the previous two stories but have them ready in case the politician needs them. Each political story needs to be tailored to the individual.

Who Will You Tell Your Story To ?

In the mass media era the default assumption could be, ‘get as much public awareness of your campaign as possible to be as effective as possible’. Underlain by ideas about democracy and the power of ‘the people’, this was a fair if not always reliable assumption. So campaign groups became media mavens and in particular, experts at feeding the ‘news media’. They learnt to anticipate the heuristic rules and reflexes of the news machine, such as “first simplify, then exaggerate”. There was little practical choice except to feed the machine, and most of the time the media would tell the story.

Online, digital and in particular social media, has changed all that, bringing opportunities and challenges. For example:

- we have moved from a world where huge-audience mass media dominated, to one of huge media choices including personalised media with many small audiences. Consequently: this has reduced common awareness and perceptions, enables audiences to live in separate worlds of attention and values and makes it harder to recruit support across such divides.

- diversification of media and the substitution of narrow-casting for broadcasting, has eroded the power of ‘the media’ to define and confirm a ‘public agenda’, and so, ‘what matters’. Consequently: “issue promotion” becomes much harder to achieve, wide attention is harder to sustain, and the significance of ‘opinion’ becomes less clear, even where it is signaled, making signals easier to ignore.

- old media and its tight relationship with political power offered a conveniently limited set of targets on which to apply pressure but diversified, networked new and social media rarely do. Consequently: ‘the media’ is gradually disappearing as an intermediate lever between individual citizens or consumers, and those with ‘hard power’ in direct control of institutions, budgets, assets and resources.

- potential supporters of ‘campaigns’ are faced with a huge proliferation of possible choices. Consequently: if the base of potential support for ‘cause’ campaigns is in limited supply, this may lead to cause-tourism and distraction, satisfying the desire to do something but reducing the probability of doing very much.

- the potential, indeed the perceived imperative for campaign groups to engage online, has reduced the perceived need to organize offline. Consequently: in common with some political parties, campaign groups have an increasingly virtual relationship with their supporters, and weak bonds may predominate.

Such factors pose challenges for organizational-level strategy in terms of engagement and shaping of networks and investment in what campaign groups do online, and, as David Babbs of 38 Degrees puts it, IRL, or “In Real Life”.

What does it mean for story telling and stories in campaigns ? To my mind it means there is a risk of becoming opinion demonstrators rather than doers. Gathering indications of support has become easy. A previous blog discussed the example of petitions. A million person paper Save the Whale petition by Friends of the Earth created news when it was handed in to Downing Street in 1970. It probably would today: that’s difficult to do. A million clicks is much easier. Yet even a million clicks seems to be getting harder to achieve, perhaps because online has spawned swarms of new opportunities.

At the same time it has become easier to talk to the converted, to people in your network who share your views. But are these people any more likely to be the most important audiences you need to reach to get results now, than before social media existed (pre 2005) ? No they won’t be but that may not be as obvious as it was in ‘the old days’ when it would be clear if, for instance, you were only being reported in the one friendly national media outlet that shared your values, while the other nine criticised or worse, ignored you.

Making Audiences

In my view if digital story telling is to be effective, a lot more thought and effort needs to go into creating and reaching audiences, and that’s not something that story-telling techniques or formats show us how to do.

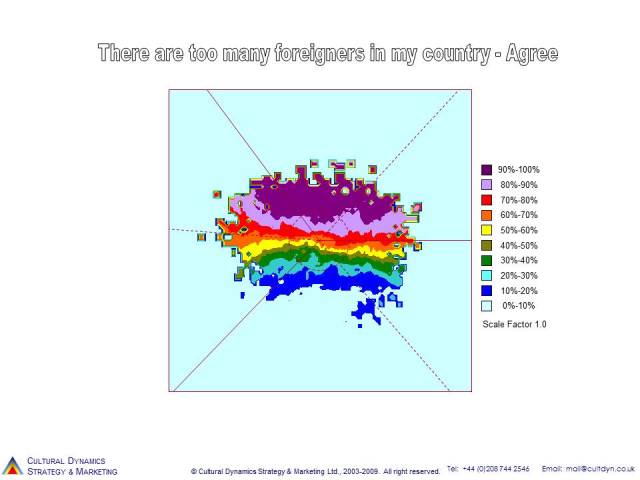

Campaign stories need to reach across silos of values and interests, and be part of real world campaign activities, making stuff happen not just talking about it. From values research I’ve seen pre- and post-digital age, it does not look as if most campaign groups are engaging with different audiences, and if evidence like physical demonstrations is anything to go by[35], it does not look as if there is more net mobilization of ‘society’ either.

Cost is a factor but the biggest challenge for campaigners is simply psychological: the requirement to get out and get to know, or at least work with and create some social bonds with, people not like themselves. To create that feeling which people sense when “the whole town turned out” and “all sorts of people got involved”.

For ‘story tellers’ this means accepting that the stories that work, will not be those that feel right to them but the ones that feel right for the audiences. Or as Frank Luntz said, it’s not what you say, it’s what people hear that’s important. Immersion in our own online echo chamber can create a womb-like comfort which insulates us from unpleasant realities, such as that our pleasingly popular online story is mainly being consumed by those who already agree with us.

A side-effect of the pre-digital, mass-media dominated world, was that limited media consumption opportunities meant that people sometimes came across things that they would not normally chose to take an interest in (particularly tv news items which are hard to avoid). In a 2000 article The Golden Age of Pressure Groups I argued that this had created a free gift to campaigners of incidental awareness, and one which was coming to an end through the fracturing of broadcast tv audiences, and dwindling newspaper readership. This effect of inadvertent awareness has been further diminished by our ability to tailor our news feeds, and by the shrinking resources and depth of the news media themselves.

Likewise, old media unintentionally created ambient ‘message pollution’. For example we might see newspaper headlines on newsstands as we passed by, or on discarded copies, or read articles wrapped around our fish and chips[36], or while sitting staring at fellow passengers hiding behind their papers and magazines on a commuter train (before we all got smart phones). This creates a campaign need to achieve similar real-life or digital effects.

New technologies such as Virtual Reality bring us closer to making media more like real-life experience, which is of course the most powerful communicator of all. A great thing but not much use unless we can get the right audiences to experience it. Creating contexts and platforms where we can tell complete stories becomes as important as being able to create them. This after all is why the movie industry has promoters, distributors and a host of other elements, not to mention cinemas, to get people to go and see a film, and does not just rely on being able to make a good movie.

I realize that even the most digital of all campaign groups, such as Avaaz and 38 Degrees, which are less like conventional clubs, societies and NGOs, and more like online brands offering an easy and quick Campaign Service, are trying to do more “In Real Life” campaigning but much more of that needs to be done. The same goes for older format more established groups. Getting onto streets, into ‘communities’, workplaces and other ‘real life’ domains, and building up strong social bonds[37] within and across values groups, is more important now than in the age of mass media.

A simple if uncomfortable way to uncover these opportunities is simply to take online away. Try planning a campaign without it, and testing out the ideas. (There is of course a latent interest, especially amongst Pioneers interested in innovation, for more In Real Life without online). Online may be relatively cheap and easy but IRL is more likely to generate stories worth telling – being story-makers so others want to tell our story.

In some ways digitalisation has brought us full circle, to a version of the pre-media era. It was always possible, when we mostly lived in towns and villages where we saw the same people rather often, to avoid those we didn’t want to spend time with but it was quite difficult to do so completely, especially if we relied on word of mouth to know what was going on. We could all be our own story tellers but we relied upon authority figures to tell us whose story to believe.

Mass media changed all that but the menu of stories was often limited, and the vicarious experiences were in common: huge numbers of us consumed the same media. Now it’s less clear who to believe, and our friends may not even be aware of the same ‘news’ as we are. Plus we can all be broadcasters but mostly to our friends

Isn’t that good ? After all many surveys show friends and family are the most trusted sources for a lot of ‘information’ or asks to do things, so social media based on such networkscan be highly effective. However that’s a potential, not any sort of guarantee it will happen. I was recently in a focus group in which a number of people who were quite regular ‘online campaigners’ explained that they rarely urged their friends to also take the actions because they wanted to stay friends. They assumed their friends were not ‘those sort of people’, or that they simply would not be interested, or that it was too difficult to explain. The last is the self-same reason most commonly given by news editors for not covering a story.

In the very old days, the arrival of a real specialist story teller was probably a special event. But even a shaman could not be in more than in one place at once, at least not physically. Mass media and digital both give the capacity to bring stories to large audiences, quickly or even in real time. Digital creates much greater opportunity to select whether or not to pay attention. As Ethan Zuckerman said in Rewire, “Our challenge is not access to information, it is the challenge of paying attention.” Thanks to common human reflexes, the potential of the internet to connect ‘globally’, instead facilitates us spending more time looking at material that is local, socially or geographically.

My guess is that the gradual slide from mass to digital media makes no net difference to campaigns because everyone else, including your opponents and everyone in between, are doing the same things, only the more connected world is also perhaps also becoming more insular. The hard graft will still be necessary to make campaigns work, and today ‘hard’ includes ‘In Real Life’ campaigning with people who you would be unlikely to meet online, as well as making strategy which involves being story-makers, not just story-tellers.

Possible Things To Do

- Try to be story-makers rather than story-tellers. Make real change that leads other people to want to tell the story of what you make happen. Be the story.

- Make it easier by investing more in In Real Life real-world campaigning activity than in story-telling, especially digital story telling.

- Make that ‘easier’ by exploring how to create campaigns without ‘digital’. The digital will arrive later anyway. Otherwise you may get stuck in the bubble.

- Remember that people pick up fragments of your story, whether told deliberately or not, and construct the rest. So make each fragment, each moment, ‘make sense’ in itself. Prioritize the audiences you need in order to make a real difference.

- Invest in expanding audience opportunities where people can ‘get’ your beautifully crafted complete stories. But sparingly and strategically as this is expensive, and very few will ever see them. Unless you get very clever, very rich or very entertaining.

- Construct critical path strategies that are about achieving objectives leading to change (ie evidence-based ‘theories of change’, not generic theories of change), and develop bespoke, tested stories to help motivate key audiences at each step. Be led by change strategy served by stories, not a strategy of story telling.

- Reach across social silos, especially online networks of ‘like’ people. Be plural to engage different audiences. Don’t waste time trying to bend a diversity of audiences to accepting stories that don’t feel right to them. Match stories against values, don’t try to change the values of the audience. Find out what does work for them, in doing what you need to make happen, and find a way to give them that, whether you are the story author, messenger, channel or not.

footnotes

[i] Thanks to Erik Bishard, Bob Rowell, Christian Tierte, Erika Roggio, Isabella Helicar Antenen, Joel Dignam, John Ashton, Jose Gavilan, Kelly Rigg, Marine Faber, Nick Buston, Philippe Duhamel and Titus Alexander. Sorry if I missed anyone.

[ii] The term ‘narrative’ is also used in another way entirely, where it means a ‘meta story’ or template which enables people who use it, consciously or not, to make sense of any relevant development and find meaning in it, much in the way that a ‘frame’ does. See for example Steven Corman http://csc.asu.edu/2013/03/21/the-difference-between-story-and-narrative/ and links therein. Such ‘narratives’ can become systems of stories that are linked by common archetypes, forms and themes, for example in cultural myths as in individualism and ‘America’, environmentalism, or any religion. Politicians frequently yearn for a ‘consistent narrative’ meaning that prospective voters will find an attractive thread running through their actions or pronouncements. The political meaning of ‘narrative’ is often a desire to connect with or to escape from a myth. In normal circumstances, creating these sorts of narratives is above the pay grade of any campaign.

references

[1] See for example pp 43-6, 155-7, 257-8, 299-300 in How to win Campaigns: Communications for Change, Earthscan/ Taylor and Francis 2010

[2] http://edtate.com/stories/

[3] http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/it-is-in-our-nature-to-need-stories/

[4] http://www.tmsworldwide.com/tms10r.html

[5] http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-secrets-of-storytelling/?page=1

[6]http://www.dana.org/Cerebrum/2015/Why_Inspiring_Stories_Make_Us_React__The_Neuroscience_of_Narrative/

[7] http://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/how_stories_change_brain

[8] http://www.fastcocreate.com/3027563/the-story-button-in-your-brain-neuroscience-study-sheds-light-on-brand-human-love

[9] http://lifehacker.com/5965703/the-science-of-storytelling-why-telling-a-story-is-the-most-powerful-way-to-activate-our-brains

[10] http://www.lane4performance.com/insight/blog/storytelling-how-neuroscience-demonstrates-the-effectiveness-of-stories/ – and see references

[11] See my book What Makes People Tick https://threeworlds.campaignstrategy.org/

[12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/When_Prophecy_Fails

[13] Daniel Kahneman and Amon Tversky, Thinking Fast and Slow, Penguin 2012

[14] http://www.amazon.co.uk/Story-Substance-Structure-Principles-Screenwriting/dp/0060856181

[15] https://www.writingclasses.com/toolbox/ask-writer/whats-this-business-about-chekhovs-gun

[16] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monomyth

[17] http://www.amazon.co.uk/The-Writers-Journey-Christopher-Vogler/dp/0330375911

[18] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Power_of_Myth

[19] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monomyth

[20] http://narrativefirst.com/articles/not-everything-is-a-heros-journey

[21] http://dramatica.com/theory/book/plot

[22] http://www.dailywritingtips.com/narrative-point-of-view/

[23] http://www.robertmills.me/narrative-story/

[24] http://ingridsnotes.wordpress.com/2011/09/12/to-plot-or-not-to-plot-part-1-terminology-and-the-difference-between-narrative-and-story/

[25] http://hacktext.com/2011/09/story-vs-narrative-vs-plot-1205/

[26] http://www.booncotter.com/story-plot-and-narrative-not-the-same-thing/

[27] http://www.ehow.com/info_10038404_difference-between-narrative-story.html

[28] http://www.vanadia.com/storytalk/talks/story-vs-narrative/

[29] http://www.how-to-write-a-book-now.com/writing-an-outline.html

[30] http://www.robertmills.me/narrative-story/

[31] https://uk.answers.yahoo.com/question/index?qid=20070919064055AArsck0

[32] http://www.slideshare.net/cfgstania/todorovs-theory-7100632

[33] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claude_L%C3%A9vi-Strauss

[34] R L Wing, The Art of Strategy, Doubleday 1988

[35] There can be no doubt for instance that climate change merits a huge political response. The September 2014 Peoples Climate March (“To Change Everything, We Need Everyone”) brought over 400,000 onto the streets of New York, with lots of smaller events around the world. Yet Earth Day 1970 saw a million-strong ‘protest’ in New York, while 20 million took part in events across the US as a whole. Earth Day 1990 allegedly managed to ‘mobilise’ 200 million globally.

[36] if you were British, and before that was stopped on health and safety grounds

[37] https://threeworlds.campaignstrategy.org/?p=116

updated Jan 3 2016

discarded crabbing buckets and lines picked up from Wells Quay on one summer morning

discarded crabbing buckets and lines picked up from Wells Quay on one summer morning