Chris Rose, August 27, 2024 – https://threeworlds.campaignstrategy.org/?p=3115 download this post as a pdf, here

In July 2024 the UK got a new Labour Government. As part of it’s preparations for fighting the election, the Labour Party cut its ‘Green Prosperity Plan’ to invest £28bn a year in a green transition, by 80%. We also got a spring and early summer almost without insects, much to the alarm of a small section of the population who follow these things closely but with no discernible political reaction. At midsummer, London saw the largest ever mobilisation of nature groups, in the 60,000 strong ‘Restore Nature Now’ march. It was ignored by the BBC. The day after the election, David Attenborough got a standing ovation when he visited the tennis at Wimbledon. What’s this say about the prospects for nature under Keir Starmer’s Labour?

For decades UK politicians of both main UK Parties have treated the environment and particularly nature, as a politically optional and ultimately disposable ‘priority’. I’ve reached the conclusion that until nature is less invisible, and more embedded and expressed in everyday social culture, this will remain a limiting factor because Westminster politicians not-so secretly believe the UK population doesn’t really care that much. To change that, Britain’s nature groups need to focus on culture more than policy.

In this post I look at the political situation for nature and the environment under Keir Starmer’s Government, and at Westminster political culture. A subsequent post will look at what could be done to widen and deepen connection to nature as part the culture of UK society.

Introduction

On the morning of 5 July, the day after along with most of the country, campaigners for nature and environmental protection heaved a sigh of relief. The unpopular Conservative government was gone in a landslide General Election victory for Keir Starmer’s Labour Party, which secured 412 seats, a huge majority of 172.

Environmentalists had endured 14 years of broken promises, false starts and regulatory failure on issues from climate change to food and farming, to water pollution and nature protection, punctuated by periodic attempts to consolidate right-wing support by denigrating and reversing pro-nature, pro-climate policies, with ruling politcians even attacking their own nature agency, Natural England.

It’s a bizarre feature of this sad story that UK public opinion was in favour of stronger environmental action throughout, and Conservative voters were if anything, more in favour than Labour voters. Why this had so little effect on government nature policies has to do with the lowly and untethered place of nature in UK political culture, and that in turn, reflects a social culture, informing political predicates and convictions, which has a very limited connection to real nature.

For generations, Britain’s environment movement has succeeded in protecting thousands of individual nature sites, produced swathes of reports and analyses of issues and now, has taken to cross sector mobilisation in marches. But with it’s influence largely confined within its own base, that not been enough to stop politicians treating environment as a marginal, optional concern.

Consequently with nature almost absent from social connections between voters and their political representatives, government environmental policies and the outcomes they seek to achieve, are only weakly accountable to public opinion. Culture, as they say, trumps both process and strategy. For most of our politicians, nature in UK culture is socially invisible, and thus politically disposable.

This blog explores why in my view, UK campaigners and advocates need to look beyond policies to social culture, meaning popular culture, what people do and value doing. Without that, nature can’t be really restored in the UK, rather that just celebrated as a nice-to-have concept. Keir Starmer is said to be a ‘committed environmentalist’ but he is also boxed in by many constraints which we have to be realistic about. All the more reason to make a start on the long game of changing the social invisibility of nature now. It does not involve inventing a wheel: many ingredients for doing so, already exist.

A Nature and Politics Strategy Framework

Here’s a crude strategy framework to show how I at least, see the issues discussed in this paper. It’s specific to the UK and particular England, where almost all key nature related policies are directly or indirectly controlled from Westminster. The content and implementation of nature policies is determined by Westminster Parliament, Government and Whitehall Departments and below them, agencies they control. Behind those policies lie the ideas politicians have about how important nature really is, part of Westminster culture. Those are somewhat tenuously derived from wider social culture. NGOs can try to affect all three.

The default focus of UK NGO political efforts has been on Westminster and Whitehall. Political culture, particularly among MPs, is quite impervious to external influence. Political and Parliamentary tradecraft is conservative ‘with a small c’.

There is abundant evidence, a lot of it collected by the environmental NGOs themselves, that the default approach has been an historic failure and UK nature is one of the most depleted in the world.

My conclusion is that this is doomed to continue so long as the political culture in Westminster remains cynically disbelieving about the importance of nature to voters, and the only realistic way to change this, is bottom up social evidence of nature being culturally important to voters, and not just to representatives of the ‘NGO lobby’.

Part 1: The Place of Nature Under Keir Starmer

Wimbledon 2024: A Good Omen?

David Attenborough receives a standing ovation at Wimbledon, 5 July 2024

On the day after the General Election, Sir David Attenborough received a standing ovation as he took take his place in the ‘Royal Box’ at the Wimbledon tennis tournament. The 74 seats in the Royal Box are invitation-only from the Lawn Tennis Association and stuffed with top rank celebrities, the rich, powerful and famous. Outside the Royal Box another 14,000 mainly rich and influential people make up the rest of Centre Court, and it was these people who rose to give Attenborough his standing ovation. Millions more (not me) avidly follow Wimbledon on tv or online.

When It Hits the Fan is an interesting BBC podcast presented by corporate communications gurus Simon Lewis (ex Buckingham Palace) and David Yelland (ex Sun newspaper). I recommend it. In the July 2nd episode “Why PR loves Wimbledon”, Yelland described passes into Wimbledon as the “golden tickets” of UK PR, and the Royal Box as “probably the best bit of PR in maybe the entire world … part of the soft power of this country”. In this country Wimbledon is a cultural fixture , an occasion for the UK to feel reassured and good about itself.

So was Attenborough’s Wimbledon endorsement, seen on TV and online by millions, a good omen for nature under Starmer? It was a cultural moment but they were celebrating the David Attenborough, not nature. It was best summed up by a commentator for Australian Broadcaster @9NewsAUS who said “for much of his 98 years, Sir David Attenborough brought the world’s wildlife into our homes”. The Daily Express described him as ‘revered’ and ‘iconic’.

All true although as has been discussed many times, for most of his career Attenborough brought us living-room nature-tainment without revealing the reality of environmental destruction that was eliminating the very nature shown in his programmes. Within the BBC it was known as ‘the bubble’: nature escapism, a treasured part of domestic tv culture.

To be fair to Attenborough, it’s also true that his 2017 series Blue Planet II, made well after he had become a global tv phenomenon, broke that mould by showing the impacts of plastic and did a lot of heavy lifting to enable plastic campaigns. And, that in recent decades he departed from his insistence that he was ‘just a film-maker’ and became an overt conservation advocate.

Chris Packham: ‘Restore Nature Now’

A better bellwether of Wimbledon’s commitment to restoring nature would have been to invite Chris Packhamto the Royal Box. (Or possibly the charismatic Feargal Sharkey, musician and fly-fisherman turned clean rivers activist – of whom more below).

Not world-famous but well known in the UK, Packham (age 63) is a zoologist who built a following through fronting popular TV programmes from The Really Wild Show in 1986, to BBC’s Springwatch (since 2009). Packham is spikier than the emollient Attenborough, and has become increasingly activist.

Like Greta Thunberg, Chris Packham has Aspergers and “says it like he sees it”. In 2015 he called out major UK conservation groups for their weakness on Fox hunting, Badger culling and the perscution of Hen Harriers. His home has been attacked by arsonists and he has been villified by pro-hunting groups. Perhaps down to him, the popular Springwatch series has changed from just promoting UK natural history to actively calling for conservation action.

Packham can also take credit for gradually unifying the UK’s diverse collection of environmental NGOs in public and demure demonstrations. In 2018 he organised a Manifesto for Wildlife and delivered it to Downing Street with a march of 10,000 people, ‘The Peoples Walk For Wildlife’.

Chris Packham’s Walk for Wildlife, 2018 (photo www.dailypost.co.uk)

The 2018 March was something of a watershed in that it was supported by the main conservation NGOs as well as animal welfare groups, who then backed a second Packham walk slated for November 2022. That was postponed three times due to rail strikes, and finally cancelled in 2023 after Packham attended another family-friendly four-day event, The Big One (April 2023) led by Extinction Rebellion, with a consortium of groups including Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace but without the main conservation NGOs. XR said 60,000 people took part.

This year Chris Packham got together 350 organisations including businesses, for Restore Nature Now (RNN) another march from Hyde Park to Westminster, on 22 June. It was billed as the country’s ‘biggest ever march for nature’ and had been planned months before the moment when, on May 22, UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak surprised almost everyone by calling a General Election for July 4. The police estimated 60,000 took part. Some of the organisers said more. The most A-list participant was actress Emma Thompson.

Emma Thomspon, Chris Packham and pro-nature group leaders front the Restore Nature Now march, 2024. Image from www.restorenaturenow.com

Sky News, ITV News, Al Jazeera and other broadcasters covered RNN and it was covered in the press but the BBC did not turn up, prompting a spate of angry and disappointed complaints on Twitter (X) and in other social media.

“BBC news didn’t even cover the restore nature demo of 60,000 … why?” – @BellaDonnelly; “Shameful absence of BBC News …” – @NatureNerdTech; “Shhh! @BBCNews thinks 60,000 or more protesting in central London to #RestoreNatureNow never happened … But it’s OK … @BBCNews features an ugly dog, and a boxer wanting his son to be an accountant” – @artgelling; “where is your coverage of this pivotal pre-election event?” – @dmokell

More complaints poiting out covergae of Taylor Swift, previous BBC failures and accusing the BBC [fairly] of having a “biodiversity news blind spot”.

Not News

Internal BBC politics probably played a part but for those of the organisers who understood news, being ignored by the BBC could not have come as a surprise. You didn’t have to be David Yelland and Simon Lewis to see the basic problem. Standing in Parliament Square at the end of the march, as people around us complained about those media present focusing on Emma Thomspon and asking her if she supported Just Stop Oil throwing ‘orange paint’ onto Stonehenge (that happened three days earlier and was condemned by Rishi Sunak and Keir Starmer), a campaigner friend said simply: “if they wanted news they should have provided some: there wasn’t any”.

Organisationally, to go from 10,000 to 60,000 was an achievement but it wasn’t news. Plus news is about an interesting or surprising twist on something people already understand, so the media focused on the most famous person involved and asked her about something controversial because if nothing controversial or consequential is happening, such as some form of disruption, then someone well-known saying something controversial, is second best. News journalists look for the conflict in events. If Thompson struggled to move the conversation on, perhaps it was because after the slogan ‘restore nature now’, chanted on the march, there was no single stand-out demand or consequence but a five point rather general and predictable set of ‘aims’, directed at politicians in general, too long to get into a soundbite:

Any one of those points could have been sharpened and directed at particular politicians or other groups, so as to demand a response but none were, nor in the context of an imminent election, did they directly relate to voting.

Beyond demonstrating numbers, it wasn’t clear to me at least, what was at stake, or where the political jeopardy was for any politician in not doing any more than sympathetically acknowledging the concerns of the well-tempered marchers. Is this how environment groups should try to influence the Starmer administration?

The Numbers Game Trap

Depending on what the organisers were hoping to signal, perhaps the most unfortunate fact was that if you are holding a ‘mass protest’ in London, the media idea of “biggest ever” is a lot bigger than 60,000 or even 100,000.

The 2003 Stop the (Iraq) War protest on the same London route, was put at a million strong by the BBC. The 2019 Second Referendum march against Brexit, also in the same spot, was reported by Sky News as a million. I was at both and you could see the police starting to lose control as marchers spilt out from the organised routes and flooded through side roads and parks towards Parliament.

From Sky News

That loss of control registers politically: the sense of being physically overwhelmed by manifest public opinion is visceral. If such a march happens at the weekend, by Monday morning, advisers, officials and Ministers across Whitehall and Westminster will be in “do we need to recalibrate?” mode. If a march passes off unremarkably, it won’t be noticed. If it fails to match the organisers public expectations, that will be noted down for future discounting of your claims. A case of, to quote Josef Stalin, “how many divisions does the Pope have?”.

It’s all the more awkward because the UK green NGOs still like to claim that between them they have 8 million members, and imply that politicians should therefore listen to them. In one sense that is probably true but if it’s in fact 8 million direct debits and includes ‘family members’, that’s not 8 million voters. Mark Avery, a colleague of Chris Packham at Wild Justice, has argued that in reality the combined membership of the NGOs may represent just 500,000 ‘committed’ individuals.

Avery, who spent years working for the RSPB, wrote in his Reflections “if government really believed that the wildlife conservation movement had 8 million supporters it might well take a lot more notice of what it said”.

https://www.youtube.com/live/vqjSaJ9z9WA Feargal Sharkey addresses the Restore Nature Now marchers.

As the march ended, former Undertones singer and fly-fisherman turned rivers campaigner Feargal Sharkey delivered a firebrand “we’ll be back” speech with cadences of J F Kennedy:

“I need you to make a promise today. If, under a new government, (these problems are) not resolved …. if the needs be, promise me you will be back here again, two times more, three times more, and if need be we will be back here one hundred times and bring a million people”.

As Sharkey implied, if you do embark on a numbers game, you had better show signs of winning by upping the turnout. A million is a lot more people who need to be persuaded to take a day off from fishing, family weekends or pleasant trips of nature reserves or National Trust tea rooms, to join a political march in London. It’s may be impossible without pinning a march to an impending cliff-edge political decision, as applied in the case of the Iraq War and Brexit. But in truth the environment groups could get a long way without needing any qualitative change in strategy. Just more effort and organising might raise the turnout say, tenfold, to 600,000. The NGOs have the money and mandate to do that, if they have the will.

Turning out 600k in 2025 would at least pass the Avery Threshold but there are other issues than time and cost which I’d suggest are more significant, and underly the very reasons the environment movement struggles to gain real political traction on nature. These do require a qualitative change, with a focus on culture beyond Westminster, indeed beyond what’s obviously political. {See part 3}.

In August Sharkey announced a ‘March for Clean water’ in London on 26 October, supported by Surfers Against sewage and others.

The Business As Usual Trap

After the election, The Independent reported that some of the organisers of Restore Nature Now had re-addressed its five demands to Prime Minister Keir Starmer. The Independent noted that ‘groups plan a “mass lobby” of Parliament ‘which aims for thousands of people to travel to Westminster to talk to their MPs’, and ‘the first UK Nature Conference’’.

It also reported: ‘A Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs spokesperson as saying:

“Nature underpins everything. That is why this government is absolutely committed to restoring and protecting nature. We will ensure the Environmental Improvement Plan is fit for purpose and focused on delivering our Environment Act targets, improve access to nature and protect our landscapes and wildlife.”’

This is the Business As Usual trap: trying to address the problem of inadequate policy or implementation by arguing about policy, and responding to an invitation to discuss plans,policies and process with government, rather than changing politics and culture which create the preconditions for government attitudes to nature.

Of course some policy developments do have to be engaged with but the greater the focus and effort put into those, the greater the risk that more significant things not already on the policy conveyor belt, go un-addressed. The fact that the Starmer administration has shot into action with announcements on climate, energy and water pollution, and is currently positive to most NGOs, may make this all the risk all the more acute.

In July, instructed by Starmer’s enforcer Pat McFadden MP to talk up the challenge they were inheriting from the Conservatives, the new Ministerial team issued appraisals which were s startlingly and deliberately blunt. Health Secretary Wes Streeting announced “the NHS is broken”. Steve Reed, the new Environment Secretary declared “nature is dying”: powerful words of alignment with the perceptions of environmentalists.

Despite such encouraging mood music, simple mechanical factors of bandwidth and loyalties will work against the environmental NGOs having much impact on the Starmer Government’s green plans in its first year, and maybe longer. After so long in the wilderness of Opposition, the new Labour Government is not short of policy ideas, and those produced within the Party will take priority. It’s also short of money, partly as a result of boxing itself in before the election, with self imposed ‘rules’ on tax, spend and borrowing, as it tried (successfully) to avoid showing the Conservatives an open flank on the economy.

So there will not be much space or appetite to consider alternative policy ideas until the shine has well and truly come off some of its initial agenda. Ironically a tired old government unexpectedly returned to office may be more likely to adopt new ideas, as it’s tried so many that haven’t worked, it’s no longer particularly attached to them.

We were in a similar position with the old New Labour back in 1997, which also had a large majority, and also had spent a long time out of power, and struck a very different tone to the outgoing Thatcherite Conservatives. When Tony Blair spoke of a new dawn breaking on the morning after, he was channelling a national mood. Anything seemed possible, and there was some money. Poor Keir Starmer has also brought relief but more like the fire brigade finally turning up to hose down the wreckage of a burning home.

Orange Wall, Green Belt, Grey Belt, Brownfield And The Greens

If opinion polling is discounted, what difference might the actual votes cast make to how environment fares under Starmer?

Immigration, cost of living and most of all, the state of the National Health service were battleground issues in common between Conservatives and Labour at the election, with simple despair at the broken state of the country under the Conservatives, Labour’s strongest card. Nature and climate did not really feature. Now there is a Labour Government, a lot of non-featuring issues will re-emerge.

Outside climate and energy policy where even after Reeve’s raid on the funding, Ed Miliband’s plans will probably keep environmentalists on side, two buckets of issues may bump up the political salience of environment for Labour in government. The first could be called Belt issues, and the second, the Wall issues. The latter might even convince some calculating Westminster politicians that a ‘nature vote’ is becoming a real thing.

Belt Issues

From a conventional political perspective the most obvious ‘green’ flashpoints for Labour to have to deal with in Government centre on its long-trailed intention to take on ‘NIMBY’ (Not In My Backyard) opponents to development, particularly on housing and new powerlines to distribute renewable energy. Labour’s hopes for growth rest on pushing through such developments.

In spring 2024 Labour adopted the term ‘Grey Belt’ originated, presumably as a device to stimulate business, by development consultants KnightFrank. They claimed to have identified 11,000 sites covered by longstanding ‘Green Belt’ but which are in some way ‘grey’, for example previously developed. Labour’s favourite example, was disused petrol stations. (The Green Belt planning designation was originally designed to prevent ‘sprawl’ and the coalesecence of settlements and ‘defending the Green Belt’ long ago became a NIMBY rallying call in more prosperous, usually Conservative voting areas).

As simplifying media-friendly handles, Green Belt and Grey Belt now sit alongside ‘Brownfield’. Focusing development in Brownfield, usually taken to mean previously developed land in urban areas, has been the favoured place to put more homes, for groups like the CPRE (Campaign for the Protection of Rural England), and rural or anti-urban lobby groups like the Countryside Alliance, Country Landowners Association, and the NFU (National Farmers Union). To varying degrees all those have traditionally leant to the Conservatives rather than Labour.

So Labour might hope its tricoloured triangulation, described by Simon Lewis as “very clever”, lines up the Conservatives as the political losers in the anticipated bushfires of local opposition to its drive for economic growth through development.

An issue for nature conservation groups is that many Brownfield sites are effectively prewilded islands of landscape, in some cases far richer in nature than 90% of the ‘rural’ farmed landscape. Many politicians and most of the political media have absolutely no idea of this because they have almost no ability to read nature, and assume that if it looks green, that’s better than if it looks brown.

Up for sale – ‘brownfield’ ex industrial land at Swanscombe Peninsula, just east of London, and one of the most nature rich sites in the UK (not in the Green Belt)

One brownfield case described in a previous blog is Swanscombe Peninsula in urban North Kent just outside London. Because it’s a complex of old marshland which was enveloped by housing before intensive industrial farming took hold, and old mineral workings which left a legacy of very infertile soils, Swanscombe Peninsula is one of the most nature-rich places in the UK. Following a vigorous campaign led by local groups and backed by a raft of national conservation NGOs (including CPRE), it was designated a SSSI in 2021, leading to plans for a giant theme park to be abandoned. (Although that didn’t stop Savills, the giant estate agent, from describing part of it as having “scope for development” when the site was put up for sale shortly before the 2024 election).

Deftly handled, Labour in government could navigate these granular and complex place-based issues and avoid much political damage. Done badly, it could get itself into a right mess and alienate a lot of its 2024 voters, especially recent switchers to Labour.

Wall Issues

The 2024 election produced another colour coded addition to Britains political lexicon, the ‘Orange Wall’, to add to Blue Wall and Red Wall.

LibDem leader Ed Davey gained national media attention (normally the LibDems are ignored) by a series of one-man stunts that usually involved plunging into water. The LibDems campaigned on water pollution. They enough seats to create a sea-to-sea ‘Orange Arch’ in Southern England.

This slightly joking handle refers to the swathe of seats in Southern England won by the Liberal Democrats, who ran a geographically focused campaign successfully aimed at the now largely demolished Conservative ‘Blue Wall’, with its Remain-leaning, more liberal Conservative voters. Many switched to LibDem, and some to the Greens or Labour. The LibDems won 73 seats, a record for recent years.

Voters switching between 2019 and 2024 – More In Common: General election 2024 – What Happened? Webinar 8 July 2024

The Orange Wall may be significant for nature politics because it was almost the only part of the country where environmental concern played an obvious part in the Conservative wipe-out. Although only 17% of LibDem voters put ‘their policies on the environment’ as one of three reasons they voted for the party in 2024 [below] my guess is that this is probably a fairly true representation of the wider ‘nature vote’ in the UK. [Before the election The Wildlife Trusts suggested there might be a ‘nature majority’ in 28 UK seats, by deducting the number of their members from a predicted majority in each seat, on the basis that 84% of Conservative voters were dissatisfied with their Party on nature issues].

More in Common also found that climate and environment was a top five issue across all voters and in the top three for Labour and LibDem voters (20)% (below):

From More in Common climate and energy analysis, 2024 General Election

From More in Common climate and energy analysis, 2024 General Election

The LibDems and the Greens ran with much stronger environmental commitments than Labour and say they will now try to use their increased influence in Parliament to strengthen Labour’s environmental agenda. River and marine pollution from sewage, and from intensive farming, was a big issue in many of these areas. It’s currently the single environmental issue with potential to make some lasting impression on cynical Westminster politicians during the Starmer Government.

The Greens also took North Herefordshire, a very conservative rural seat, where mainly agricultural pollution of the River Wye had become an iconic battle between local and national environment groups on the one side, and agribusiness, Water Companies and the Conservative Government on the other.

Unlike planning issue conflicts which will be very case-by-case, the water pollution issue which involves just a handful of giant and unpopular private water companies, and its possible extension into rethinking policies on farming including the failure to resolve the UK’s chronic Bovine TB disaster and badger culling, and the potential role of rewilding, is likely to be the focus of renewed national environmental campaigns. Getting on the wrong side of this could be problematic for Starmer’s Labour Government because it is eminently ‘campaignable’.

From More In Common: General election 2024 – What Happened? Webinar 8 July 2024

Finally [above], the Greens came second to Labour in 35 seats. In areas with a high proportion of university educated younger voters concered about the environment, the Greens could become a more significant threat to Labour at a subsequent election. Which also means there are 35 Labour MPs looking over their shoulder at the Greens.

UK environmental and nature campaigners could be kept very busy trying to maximise gains on such issues but my guess is that until nature is far more embedded in social culture in the UK, progress under Starmer will look rather like progress under previous administrations.

Part 2: The UK’s Nature-Cynical Political Culture

Few UK politicians dare to directly speak out against ‘nature’ but by their actions, and private utterances, it’s clear that the prevailing political culture of Westminster is to regard nature as an optional nice-to-have and not a real-terms political imperative to deliver on.

We’ve Been Here Before With Labour

In 1997 the iconic domestic environmental issue inherited by New Labour was road building. Since the Twyford Down campaign at Winchester in 1992, the direct action based ‘roads movement’ had won considerable public support, and the Conservatives downsized their roads programme twice, while also crushing the movement by changing the laws on protest.

One of the Roads Protest campaigns – against the M11 link road at Wanstead in London. In 1993 a 250 year old Chestnut tree on Georges Green, was defended by locals and protestors in a battle with 200 police, before being uprooted. A tree house was built in the tree. It received its own postcode and 400 letters. In the end the road did not require the tree’s space and it’s remains were left.

John Prescott, was Tony Blair’s wing man connecting with the Old Labour base and Trade Unions, and a passionate believer in more sustainable transport, especially buses. In 1997 Prescott agreed with NGOs and analysts that roadspace should be reduced and better public transport introduced to induce motorists to switch ‘modes’. It promised a direct reversal of Thatcher’s vision for ‘the Great Car Economy’ and her ‘greatest road building programme since the Romans’. Environmentalists were hopeful.

1998/9 – John Prescott’s plans to prioritise public transport over road building were partially successful – use of public transport went up but the expansion of roads and road traffic continued

Prescott produced a White paper calling for a “renaissance” in public transport but Blair was wary of upsetting motorists and had other legislative and spending priorities. By 2000 Blair’s government had planned 360 miles of new motorway and industry demanded 465 new ‘by-passes’, many of which got built and looked very like motorways.

Right now Starmer is serious about ‘winning back trust’ for government and the environment lobby may be part of it, until they are not. In the end, it will come down to priorities. Starmer has already demonstrated how this might work on the environment.

Shredding the £28bn

Keir Starmer became Labour leader in 2020 and was criticized for a lack of big clear ideas. To great enthusiasm at the 2021 Labour Party Conference, Shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves produced a big idea: the Green Prosperity Plan (GPP). It was to be a smaller UK version of Joe Biden’s ‘green-deal’ Inflation Reduction Act, environmental action sensibly framed as economics and jobs. Reeves claimed she would be the “first green Chancellor”. It didn’t last.

The name GPP is already largely forgotten but Reeve’s pledge to borrow to invest £28bn a year for five years in a net-zero transition, has not been forgotten. As Labour’s flagship economic policy, it was mentioned hundreds of times, until she dropped it in June 2023.

Reeves blamed the 45-day Conservative Prime Minister Liz Truss for having ‘crashed the economy’ (almost nobody except Truss argued with that), interest rates had rocketed and there wasn’t enough money. The £28bn might build up over time. In February 2024, after painful but internal arguments, Starmer and Reeves quietly briefed a few journalists that only £4.7bn a year would be spent, a reduction of over 80%. Labour decided to make a virtue of dropping the £28bn to prove that their fiscal rigour came before green virtue: a tactical decision which implied they believed voters thought likewise.

£28bn would have been about 90 times the budget of conservation agency Natural England but it’s not a lot relative to government spending. In 2023 government Departments were allocated £558billion, of which £28bn would be about 5%, and £4.7bn, 0.8%.

Compared to the UK economy as a whole (GDP of £2.27 trillion or £2,270bn), it’s just 1.2%. To give it a real world comparison, according to the Horticultural Trades Association, £28bn is slightly less than annual contribution to GDP of the ‘ornamental horticulture and landscaping’ sector, at £28.2bn. So £4.7bn is about what the nation spends on ornamental horticulture and landscaping in two months.

Elements of the £28bn plan remain, such as Great British Energy, a state owned renewables company, which is a hugely popular idea. Other bits have gone or been severely downsized. There has been some criticism, especially from energy industrialists and economists who fear that the dramatically reduced investment cannot deliver the green energy transformation which Labour plans, such as fully decarbonizing electricity by 2030. Outside the policy communities, my guess is that the wider public were probably a bit disappointed and not surprised, or didn’t notice.

Personally I was not surprised at the way Labour abandoned its £28bn GPP pledge so lightly, and chose to drop a big ‘green’ policy rather than rule out spending in other areas. Doing so matched the default political culture amongst Westminster politicians that environment could be safely, even beneficially ditched, if that became expedient.

[it’s not just Westminster – on 25 August, to the dismay of nature groups, the BBC reported that Scottish Government Ministers had told Councils to divert £5m from the small Nature Restoration Fund to help fund new public sector wage settlements].

According to the FT, although Starmer wanted to keep the £28bn pledge, ‘election coordinator Pat McFadden and campaigns supremo Morgan McSweeney, pushed hard for the number to be killed’. I’ve never met either man but nature and environment does not seem to feature in causes they have espoused, so as highly professional ‘hard headed realist’ political operators, they might share the conventional wisdom of the two large British political parties, that when push comes to shove, environment and nature are just not that important to voters, and thus politically disposable.

Even Paddy Ashdown, then leader of the LibDems, long known as the party of lost causes, once said to me with a smile, “show me the environmental vote and I’ll go for it”. (Read this article from Politico for more on Keir Starmer on climate change, if not nature).

I’m not saying Sweeney or McFadden actively despise environment groups, although there have long been those who do in both the Conservatives and Labour, the latter mainly because they see them as competition for activists and attention, or a rival ideology (as do the Greens who now have four UK MPs rather than one), as well as not being reliably committed to social causes or in tune with working people.

A friend who has been involved in the nature conservation movement since the 1970s commented to me:

“Both major parties are embedded in unhelpful mindsets. The Right is quite fond of nature , provided it owns it. The traditional left still sees it as the enemy. I read Alfred Schmidts The Concept of Nature in Marx when I was at uni, and the idea that nature and all its restrictions was – along with the bourgeoisie – what the working class had to be liberated from. In the 20th C this translated into the cliche of nature or jobs and houses – an outlook which is in the DNA of Labour and the trades unions”.

The Wildlife Trust’s poll featured on twitter July 2 2024

Before the 2024 election The Wildlife Trusts published a national poll showing most people thought the main parties were doing poorly on a range of environmental issues, and a majority thought they were at least important as other issues facing the country. At different times, polls have found similar or even stronger results, for decades. Yet the political culture of Westminster does not work in favour of prioritising action for the environment.

Culture is set at the top and emulated lower down. Culture is what we do, it’s learnt, and assumed to make sense. Young MPs learn the art of the possible from older MPs. Culture is resistant to change. Environment may be one of the great social causes of the last sixty years but in Westminster it’s not one of the ‘great offices of state’ which ambitious politicians aspire to. In fact it’s near the bottom of the pecking order.

In his revealing and brilliant 2023 account of life as an MP supporting dysfunctional Conservative governments, Politics on the Edge, Rory Stewart describes going in to see Prime Minister David Cameron and his Chief Of Staff, after the 2015 election, to be given his first Ministerial job.

‘The most junior department in government’

Stewart recalls that Cameron seemed ‘distracted’ and remembers him saying “I would like you to be …” [consulting his notes], “… the parliamentary under-secretary in the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, dealing … with issues like farming”. Cameron didn’t even know what was involved in the role he offered Stewart. His Chief of Staff had to jump in to add: “Actually, probably more with the environment”. Stewart accepted, despite knowing that it was, in his words: ‘the most junior position in perhaps the most junior department in government’.

‘Humdrum’

The lowly Westminster status of the environment in 2015 had not changed much since 1982, when fighting the ‘Falklands War’ rescued Margaret Thatcher from electoral unpopularity, leading her to declare: “When you’ve spent half your political life dealing with humdrum issues like the environment, it’s exciting to have a real crisis on your hands.”

“It’s exciting to have a real crisis on your hands”. Margaret Thatcher in a tank. (Photo Daily Mirror).

When in 2016 political scientist Rebecca Willis tried to understand why politicians in favour of climate action struggled to make a difference once elected to Westminster, she found a major factor was the sceptical, even hostile, culture. As she describes in Too Hot to Handle , pro-climate MPs soon discovered that colleagues saw it as marginal or “niche” concern. They wanted to avoid being seen as part of a “lunatic fringe” [read as the environment groups], appearing like “a zealot”, or being a “freak”.

According to conventional Westminster thinking, often repeated by the UK political media, there’s a pragmatic reason for discounting expressions of environmental concern. It’s that nature and environment have expressive support (eg in opinion polls) but not instrumental support among voters. Voters say they’d like to see more action on it but when it comes to election day they don’t vote for it, or when it comes to implementation, they oppose necessary changes, or don’t want to pay.

The intertwined nature and climate crises may be in the process of rendering the planet uninhabitable for most species and human beings but that does not translate into political advancement and career opportunities in Westminster. Put crudely, MPs may know that their voters want more action on nature but those who have ambitions to get into powerful positions, have limited interest in pressing for it.

Critics rightly point out that because ‘nature’ and ‘environment’ rarely feature in the priority offerings of major parties, voters believe politicians don’t care so mostly don’t ask for them, so these assumptions go untested and the status quo is sustained. That’s true and it’s also true that the position has changed a bit, especially on climate and energy but not yet enough to prevent decisions like Labour shredding the £28bn.

The Environment As A Disposable Commitment

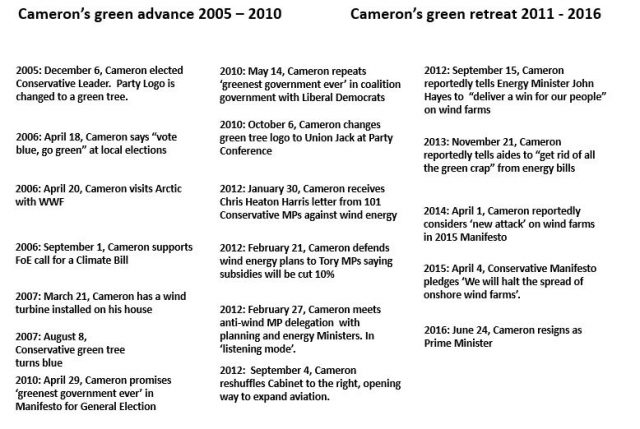

If Westminster politicians have been sceptical that voters will actually cast votes in favour of the environment as they claim, their actions suggest they believe that some can be won over by talking down the importance of environment. For decades, both Conservatives and Labour Party have blown hot and cold on green issues, right up to this years General Election. A clear and consequential example was David Cameron’s transition (see Killing The Wind Of England’ 2018) from being an advocate of onshore wind energy, with a turbine on his own roof, to effectively banning it and denouncing ‘green crap’.

From Killing the Wind of England, 2018

The fact that Conservative politicians did this despite contrary evidence from polling their own voters, is down to convictions of MPs and activists, not voters. Once a narrative becomes accepted wisdom, it can be highly impervious to contrary evidence. The conviction that voters didn’t like wind farms was so embedded that whena 2017 government tracking poll of 2000 people found just one person ‘strongly’ opposed, a Conservative MP simply refused to believe it.

After Cameron, came Conservative Prime Minister Theresa May, who committed the UK to Net Zero in 2019. Then Boris Johnson who went from being a climate sceptic to promoting his own Net Zero strategy. Then for just 44 days, Liz Truss, who moved to outlaw solar power on most farmland, approve fracking and new oil wells, and scrap hundreds of laws and funding designed to protect nature. Major nature groups threatened‘direct action’, although it was not clear what that might mean.

Then Rishi Sunak, who delayed action on car pollution, gas boilers and insulation in 2023 in the hope of convincing Working Class voters that Labour’s plans, to spend £28bn a year on green measures, would make them poorer.

Also in 2023, Labour was itself spooked by not winning a by-election in Uxbridge (Boris Johnson’s old seat) and seemed convinced by claims that anti-pollution fees attached to ULEZ, the London Ultra-low Emission Zone had been a vote loser.

‘Party insiders’, reported The Independent, had dubbed support for environmental measures as the “Uloss Factor”. By February 2024 Labour had abandoned the £28bn pledge.

July 2023 – Labour veers to seeing environment as a vote loser (The Independent)

The enormous 10,000 poll and 60 focus groups run by More in Common over the 2024 election have now shown that voters were more pro-environmental than many politicians believed.

Sunak gambled on attracting Reform Party voters back to the Conservatives by ostentatiously abandoning green policies but it failed. More in Common found the rightwing/populist Reform vote was overwhelmingly driven by opposition to immigration, not the environment. Indeed most Reform voters supported climate action. (See More in Common’s ‘Post Mortem’ analysis Change Pending report).

From More in Common, 2024

So rational assessment might now lead Labour to conclude that backpedalling on nature or climate commitments is not a vote winner. But politics is not always rational so it’s as yet unclear to me at least, what lessons Starmer’s Labour will draw.

More in Common’s post election polling showed majority support for Labour’s ‘green jobs’ renewable energy project, GB Energy across all political affinities. The risk for government must now be that the hopes raised by this idea, do not materialise, given the massively reduced funding.

More in Common say: ‘climate has become a political hygiene issue for the public – with the Conservatives’ fluctuating positions on transition reinforcing broader perceptions that the party is inconsistent on the big issues’. A hygiene issue means you don’t get a lot of credit for getting it right – it’s expected – but you are in trouble if you get it wrong. Which perhaps leaves action on energy and climate, and possibly nature, in the middle ground.

George Eaton, senior political editor of the New Statesman, argues that a gift for ‘the Common Ground’ is Keir Starmer’s ‘superpower’. Eaton cites Luke Tryl, a former special adviser to the Conservatives and head of More in Common, as believing Starmer is “is probably much closer to median public opinion than a PM has been for a long time”.

Eaton also says Keir Starmer is ‘a committed environmentalist’. Perhaps, optimistically, this will ensure that Labour now decides environment is no longer in the optional category. I hope so but I wouldn’t bet on it.

Mrs Thatcher changed Britain in many ways and she did so through actions she took, such as the allowing people to sell their Council houses, creating a whole new constituency of beneficiaries. If Starmer is to embed ‘green’ policies as beneficial at the centre, he will have to find a way to make individuals feel it benefits them. For example so they experience that renewable energy, electrification and insulation makes them individually better off. Or they register that some nature policy, large or small, makes their lives notably better.

There are limits to what the voluntary sector environment groups can do to help Starmer secure that, and elevating nature protection to a must-have rather than a nice-to-have is an even harder task than achieving success on energy. But there is a lot those groups could do to embed nature in UK culture, so politicians meet it coming from the bottom up, and this would be a good time to invest in the groundwork needed for that.

Part 3 on social culture and nature has now been published in seven sections, with a summary

download as pdfs:

[contact Chris Rose here]